"I’m not superstitious, but I just don’t think you have to say that out loud!”

“She always says, ‘I’m not superstitious, but...’ I’m pretty sure that means she’s superstitious.”

“I just don’t know why you have to press your luck.”

You might guess this conversation is a debate between One Oddgodfrey and The Next, but if you did guess that, you would be wrong. This conversation occurred between another dynamic sailing duo and set of sailing buddies. Suffice it to say, I’m not the only one.

The Modern Sailor is one who mostly eschews the superstitions of old. We no longer tattoo either a chicken or a pig on our feet in the hopes it might help us swim. We usually don’t refuse the passage of women aboard, a whole gender can’t be considered bad luck, can it?

But bananas? No way.

A coin beneath your mast? Yes, please.

A few rum-based offerings to Neptune? You would be insane not to.

After only two days in port, Sonrisa and her Armada comprised of Erie Spirit and Perry departed East London for yet another ride on the Vomit Comet. We were all looking forward to a slightly smoother passage, hoping we waited long enough to let the cross-hatched seas subside from the Southerly storm we waited out in port. Hopes high and properly dosed with sea sickness meds, we pressed out into grey, foggy skies, murky cold, and green water seas broken by the spouts of whales swimming along side us in the distance.

Within just a couple hours, we’d already smashed into something in the water with Sonrisa’s hull. “Uhg,” Andrew said as he looked overboard, trying to figure out what it might have been. “Is there any water coming into the bilge?” I opened the floorboards and peered in, hoping not to see a rush of water or even a trickle coming from the feared hull breach. “Seems dry still.” I report. Andrew nestles himself back into his beanbag.

The cold humidity gnaws its way through our foul weather gear, which is frayed, dilapidated, and about as water proof as swiss cheese might be, despite spending 4 years in our cupboards doing absolutely nothing.

I tug at some threads dangling from the seat of my pants.

Before leaving San Diego, we had invested in great foul weather gear. Gortex This, Fancy-Pants That. We used it only a handful of times on our shake down runs, sailing from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas, and maybe on a few rainy nights. But then, we entered the tropics and had no need of them any more. We lovingly folded our foulies into the cupboards, hidden from sun, heat, or any other damaging influences. But, when we pulled them out again, we were disappointed to find that much like EVERYTHING ELSE ON THE BOAT, anything rubber had turned into a paste and the threads stitching everything together were fragile as angel hair. The soles of our sea boots fell off, the fabric cracked, and nothing was functioning as it should. Why does this happen? It’s a mystery of the universe, but likely explained by some unfortunate interaction between salt water and the chemical compounds that formulate the fabric of our gear. “It’s crazy how a sailor’s mood aligns with the weather and the condition of his foul weather gear,” Andrew says, noting we are as gloomy as the gloom surrounding us.

Our vintage early 90’s radar screen glowed green at the navigation desk. It scans the pea-soup horizon on our behalf, looking through the fog to find large ships, fishing canoes, land, or other solid matter we might crash into. As the sun set, the sky darkened from its bleak white-grey to silky and opaque black, not so unlike tar they use to seal a crack in the road.

Instead of maintaining watch from the cockpit as we normally would do, we huddled below trying to stay warm outside of the drizzle and cold wind. We set alarms for every fifteen minutes, dragging our heavy, sleepy, and seasick bodies through Sonrisa’s inner sanctum to check the charts, review the AIS screen and the radar, then poke our heads out of the companion way to make sure everything still remained shipshape. Two days, sailed in fifteen minute increments, fed only by boiled ramen noodles and ginger cookies.

It was early on the third morning we neared the mouth of Knysna, a port known to wreck ships in the wrong conditions. We’d received countless advisos from local sailors up and down the coast:

“Knysna is a ship eater.”

“You should only attempt it in fair weather, an hour before high tide, no later.”

“Make sure you stay right to avoid the rocks on the left, but also, stay left so you can avoid the rocks on the right.”

“Waves break over the sand bar at the entrance, everything looks fine and then the waves will sneak up from behind and cause you to broach sideways.”

“Maybe best you don’t try.”

“But, Knysna is one of the most beautiful ports in all of South Africa!”

With all this local advice sketched into our passage log, we decided to take our chances and give it a try. “Bahwwooooh, we’ve done reef entrances far worse than Knysna!” Our intrepid, Post-Modern sailing friend declared as we paid our bar tab and headed back to the boats for our East London night-before-passage sleep. His “Not Superstitious, but…” wife scowled and shook her head brash disregard for Murphy’s Law.

Despite that, the weather offered us what appeared to be a perfect window for a two day passage from East London, but no more. If we didn’t get into port this morning, we would enjoy another Southerly blow while out to sea. Mosselbai being our next possible stop if Knysna did not pan out.

The morning of our scheduled arrival, shore was hidden from view by its shroud of fog until we were less than a mile away. Usually trailing our friends in their bigger boats by an hour or so, today was the rare morning that somehow we had sailed to the lead of the pack. This was unfortunate, as I had hoped we could send the Over-Confident Crew in on a reconnaissance mission before the Oddgodfreys made our attempt. That was not to be. This morning, Sonrisa would be the lead ship.

Just one mile offshore, we could finally see the foot Knysya’s cliff heads popping vertically out of the ocean surface. We had timed our arrival perfectly, we should have just hit high tide and slack tide was about to begin. The wind was dying back, so we started Sonrisa’s engine and listened. We knew with current and waves, the narrow squeeze through this pass, and the spines of rocks like monsters’ teeth lining the sides, we would need the engine to perform reliably.

“I think Yanmar is feeling fresh and spry.” Andrew confirms. “It’s now or never.”

As we made our decision, a pod of dolphins with grey backs and white underbellies rolled out of the cresting waves to jump and play in Sonrisa’s wake. One hundred or more came from all directions - in front of us, beside us, from behind - jumping, flipping, squeaking, and all in all, welcoming us into Knysna. “Now there is a good omen!” I exclaimed, happy for all the cheer dolphins always serve up.

I align Sonrisa’s bow with (will wonder never cease) a working leading light, guiding us in to shore. I monitor the heading and depth, hand steering to keep us aligned as gentle waves wash us right and left. Andrew watches the engine gauges, we both look forward to try to see if there are any breaking waves that will catch us unaware and roll us sideways. But, today, the ocean is calm and the waves are coming from an angle that causes no problem for our Knysna pass.

We pass jagged rocks to the left so close we can see their teeth collect the sea foam and bits of seaweed debris. We feel the strange movement as the current changes and swirls below Sonrisa’s hull when we cross over from deep ocean to Knysna’s shallow sand bar. We stay just left enough to avoid the rocks on the right.

And then! We pop through.

“That wasn’t too bad!” Andrew says.

“Shhhhhh!” I say, “the shipwrecks are next!”

Looking at my chart, there is the initial opening, a bend, and then a row of shipwrecks marked against a second narrow squeeze. Sonrisa slides along against cliffsides with arches breaching their rock face. It’s beautiful, but I can’t look for long as I must concentrate. I thread the needle between the shipwrecks, saying “I hope their masts aren’t poking up. The depth is only 30 feet.”

Soon enough, we are through, and suddenly a beautiful bay framed in emerald green covered hills opens before us. The water is now so calm, water skiiers pass as we motor in. We navigate silted river banks, watching the local markings to try to figure out exactly where we should go. Everything is quite shallow. “Should I go on the right or left of the mooring fleet?” I say. We select the right, only to kick up a slurry of mud as we slide to a soft stop in silt. I haul Sonrisa into reverse and change course. We can feel the grass tickle Sonrisa’s underbelly as we traverse the “thoroughfare”. “Good thing we’re at high tide!” we remark.

The local yacht club hails us on the radio and guides us in to take our slot right in front of the Knysna Yacht Club. We tie up behind Erie Spirit, and note the spread of post-passage hunger opening our bellies. We could smell bacon frying in the yacht club, and I could see sun slanting through the white, wood-framed windows, pouring warm onto a seat I would claim as my own. “Let’s have breakfast at the yacht club!”

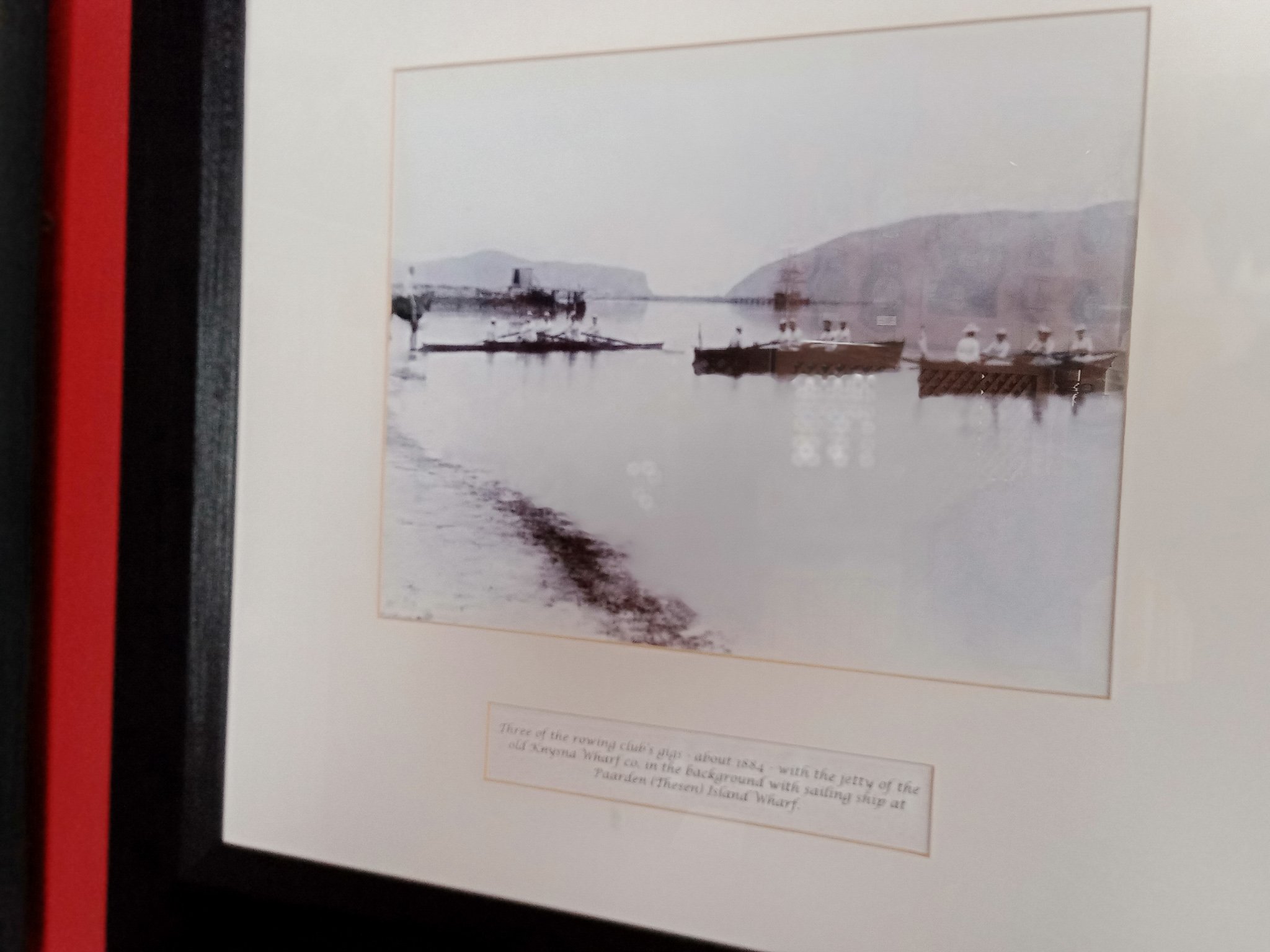

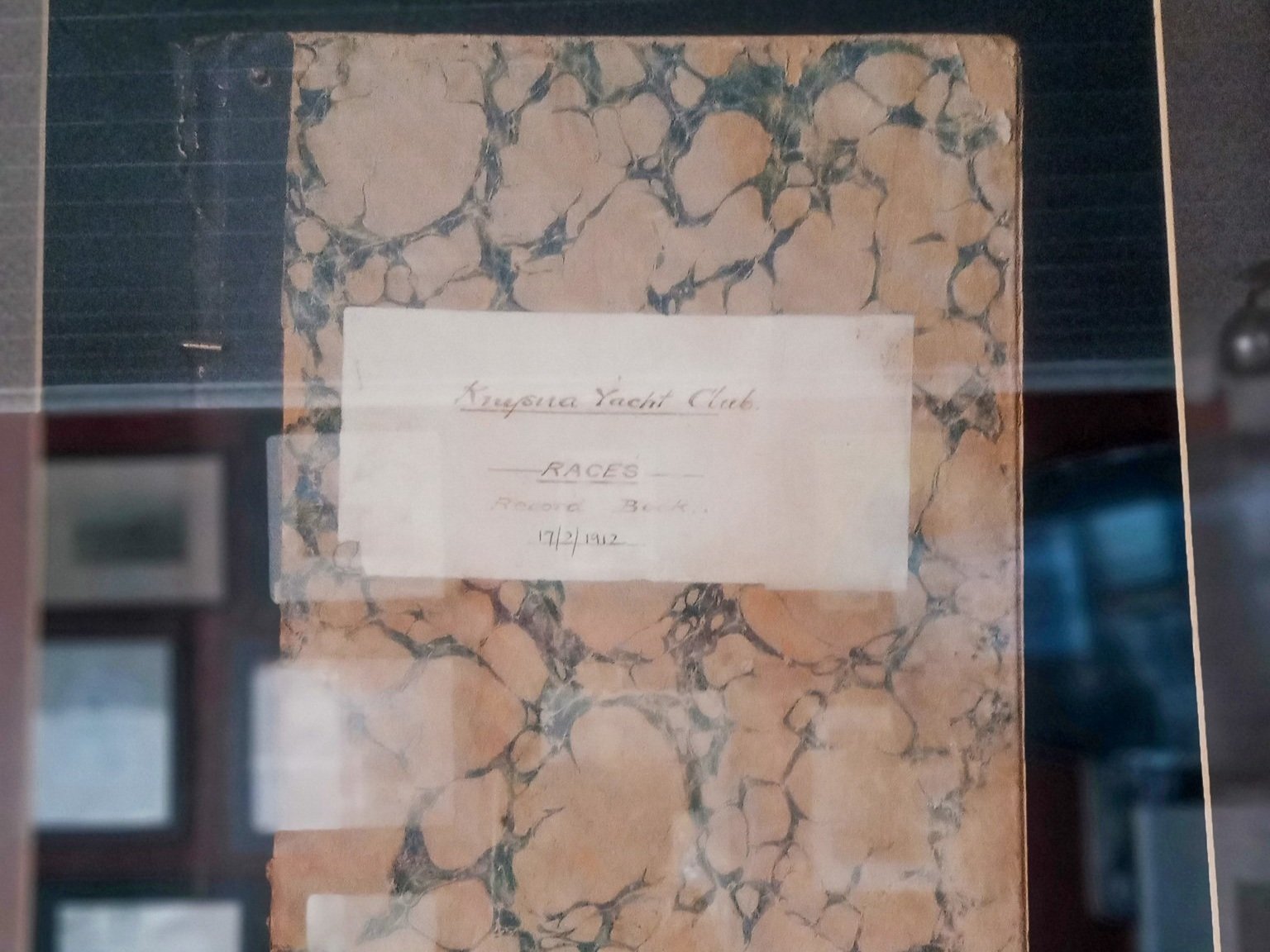

There is nothing like a post passage land-breakfast cooked by someone else. Coffee, eggs, toast, a tomato and onion jam, and mushrooms were savored in the company of our sailing friends as we all debrief our safe but foggy passage. After breakfast, I wander the yacht club, admiring the sailing trophies and big wooden ship’s wheel, each adorned with plaques polished bright clean: “1st Place, 1921 Knysna Cup” The building itself, the trophies, the log books, everything steeped in sailing history. It offers beautiful scenery with Sonrisa moored right outside.

We took to exploring the city, mostly on foot. We walked out to a café with a patio overlooking the Knysna Heads one afternoon to see exactly what it was we’d sailed through the day before. It was on this walk we began contemplating the nuances of our Post-Modern Sailing Superstitions.

“It just wasn’t as bad as everyone made it out to be,” Matt said, poking the bear.

“I’m not superstitious, but do you really have to say that kind of thing until after we successfully exit?” Jen responds.

I nod in agreement.

“So, you are superstitious, too!” Matt says.

“I see no reason why to press your luck,” I reply.

“Exactly,” JenPerry says.

“We’ve all sailed much worse,” We all agree with Matt, but then again, we also nervously fidget a little. We sip a dry, soft Pinotage Rose that smells like flowers and tastes like strawberries at a restaurant overlooking the pass while tourist catamarans dart in and out, with no concern for tide or time. I quietly plot a strategy to douse Andrew in some ceremonial rum, to cleanse him of any more “that was easy enough” speak.

Knysna Yacht Club at Sunset