If you are a tourist in Manihi, there are two things you absolutely must do: scuba and find some black Tahitian pearls. So, one morning, we headed to Ferdinand and his wife Estella’s snack shop to do some laundry in their machine, arrange for scuba diving and take a look at pearls. Ferdinand bustled around, but explained he is not working this morning until France’s football (soccer) match is over. During commercial breaks, he provides us with bags of pearls to sort through, shows us photographs, and explains the pearl farming process.

Tahitian pearls should really be called Manihi pearls, because it was in Manihi that the people first figured out how to farm pearls. Before the Manihi islanders figured out this strategy, Tahitian pearls were so rare that no normal person could own one. They take at least a year or more to develop, the oysters that grow the pearls don’t always grow pearls naturally, and when they do, they are typically misshapen. A perfect, round, lustrous black pearl used to be so rare only royalty could ever afford to own one.

In the 1980s, the people of Manihi learned to farm black pearls. They begin a regular pearl inside a specific type of abalone shell from Mississippi of all places. Once the pearl is grown, they remove it from the abalone shell and place it carefully into a Tahitian Oyster. The Tahitian Oyster continues to create the pearl, covering it with the black sheen that Tahitian pearls are known for. After explaining this process, Ferdinand gives us a big smile and says, “So these pearls are really Tahitian-American pearls!” Ferdinand breaks out old pictures of he and Estella in their pearl farming days -- including photos of them on their trip to Utah: Snowbird and Lagoon.

Ferdinand has since closed his pearl farm because he explains that it is so much work. Four pearl farms remain. Crystal and I drive ourselves nuts trying to hunt through thousands of pearls trying to compare them all and find the ones in best condition, best shape, best luster, and in the colors we like best. They are all so pretty in their own way. Even those with pits and marks are interesting. They often look the way I imagine Jupiter or Saturn to look, with colors swirling around their tiny globe.

While we look, Andrew orders breakfast sandwiches and begins playing around with Ferdinand’s pearl drill. “It has been broken for years,” Ferdinand explains, “so we can’t drill pearls for jewelry anymore.” When Kevin joins us, both Kevin and Andrew puzzle over how to get the piece that holds the pearl in place to move properly.

Hours pass, and finally, Ferdinand hears that the scuba folks are stopping in between dives to buy snacks. We meet Bernard and Martine, a French couple who moved to Manihi to open a dive company. We arrange with them to rent scuba gear and have a guided dive.

Andrew and Kevin successfully fix the pearl drill and we leave Ferdinand and Estella with a drill bit the right size for drilling pearls. Crystal and I call it a day on our pearl hunt and close our tab with Ferdinand. We could have kept agonizing over these pearls for the remainder of our week here, but you have to call it a day at some point!

A couple days later, we resume our pearl hunt. A young man of 22 has possession of 14 higher quality pearls that he wants to show us. Our schedules do not link up a number of times, but finally, we catch him at a good time and he invites us into his home. Crystal and I view the pearls and they are indeed nice. We haggle back and forth a little bit, discuss the cash price v. the price for trading various items. Eventually we settle up, both sides feeling a little beat up in the process. We pour our friend a shot of tequila, and take a celebratory selfie. Everyone’s happy; pearls are acquired.

A couple days later, Kevin is stricken by another stomach bug. When Bernard and Martine arrive to pick us up for our first scuba day, we had to leave him behind. Crystal, Andrew and I gather up our dive cards, flippers, snorkels, fins, wet suits, and snacks. We jump in the dive boat and zoom away. I am nervous. I certified for open water in 2011, had a failed dive attempt in Florida in 2011 due to murky water and high wind, dove twice in Catalina October of 2014, and that is the extent of my practice. We should have done a refresher course, but too late now. This dive is on a vertical wall of coral that drops off into 10,000 feet of water, and it is a drift dive with a current. All new for me. The dive boat rumbles along in tall swell with whitecaps. It’s a windy day. I know that Bernard and Martine are going to observe our first dive to see if we are experienced enough to dive other places in Manihi. I also know Crystal is a very good diver, so if I don’t pull my weight, they won’t take her to the good spots. My heart is in my throat and I try to slow my breathing.

We get our gear on and tip backwards into the water. Despite holding my goggles and my regulator in place, the waves rip off the strap on my goggles and the regulator out of my mouth. I struggle to get my goggles back on while kicking against the current. The weight of my tank and the weights around my waist wobble on my body in the water. I’m screwing this up already. I kick over to the rope that ties the boat in place, get my goggles back on in a rush and find my regulator. Martine is our guide today, and she pushes my BCD valve to get me to sink below the surface. I am uncomfortable, and we are sinking faster than I want to. I want to slow down and get my buoyancy under my control first.

As we go down, I pinch my nose and my ears release pressure. I am breathing too quickly, because I am nervous. I’m trying to hold on to the rope, but the current is pulling my legs back. Every time I try to find my buoyancy, I roll to the right side. The tank feels crooked and my weights are not in the right place. I struggle with my vest to adjust, but it’s not working. Martine takes my valve apparatus and pushes buttons, holds my hand, shows me fish. Like Nemo with his one defective fin, I flutter my right hand to keep myself balanced properly. Martine gives me hand signals not to swim but just float. I can’t think of the hand signal to say that all my weight is flopped to my right side, so I can’t explain to her why I am struggling so much. I know my eyes are wild. Somehow I snort salt water up my nose and down my throat and it burns all the way down. I know I’m not going to die, but for a moment, I feel like it. I might die, or I might vomit. Then, I’ll really panic. All I can think about is my ears exploding and nitrogen causing my brain to bleed when I vomit, drop my regulator on accident, then take off to the top too quickly to try to get air. I use my right hand to hold my regulator in my mouth, just in case I barf. Martine is holding my left hand, and I am rolling to the right like a beached walrus.

Crystal spots my trouble from behind, swims up and tries to tighten my weight. Martine doesn’t like Crystal messing with my gear underwater so she shoos her away, but this is enough to make Martine understand that my weight and tank are crooked. She rustles around with my gear and it is a little better. Not great, but better. Now, I can float on my own and look around at things.

My tank runs low on air first because my panic breathing has caused me to go through my air faster. We start our ascent, slowly rising. My ears feel funny, so I make the mistake of trying to pop them. Martine makes furious hand signals not to do that, as it may cause a reverse squeeze in my ears. I remember now, but don’t worry, no reverse squeeze happened. We get to the surface, and in my humiliation I climb aboard the dive boat. I failed. I definitely did not hold my weight. I think of my Scuba-Sensai Russ; he would be so disappointed in me. Tears sting my eyes. Crystal sees me, “Are you about to cry?” I say “No, I am crying.” She laughs. “The next one will be better. You just needed to get the first dive jitters out.” I’m not so sure; I am so embarrassed.

We eat chocolate cookies, drink orange juice and head with the dive boat to a second spot. The waves and wind are still high. This time, there is nothing to tie the dive boat to, so we have to fall back out of the boat while it is still slowly under way. Martine pinches her forefingers to her thumbs on each side, the international signal for “find your zen.” I smile, and nod. Martine adds another 2 kilos of weight to my belt. This time, I bend forward to rest my weight belt on my back and cinch it down as tight as it possibly can go. I am merciless. I don’t want anything wiggling around down there again. I adjust my tank vest carefully. I get everything tight. I hoist myself from the bench to the edge of the boat. I hold my mask and regulator tighter.

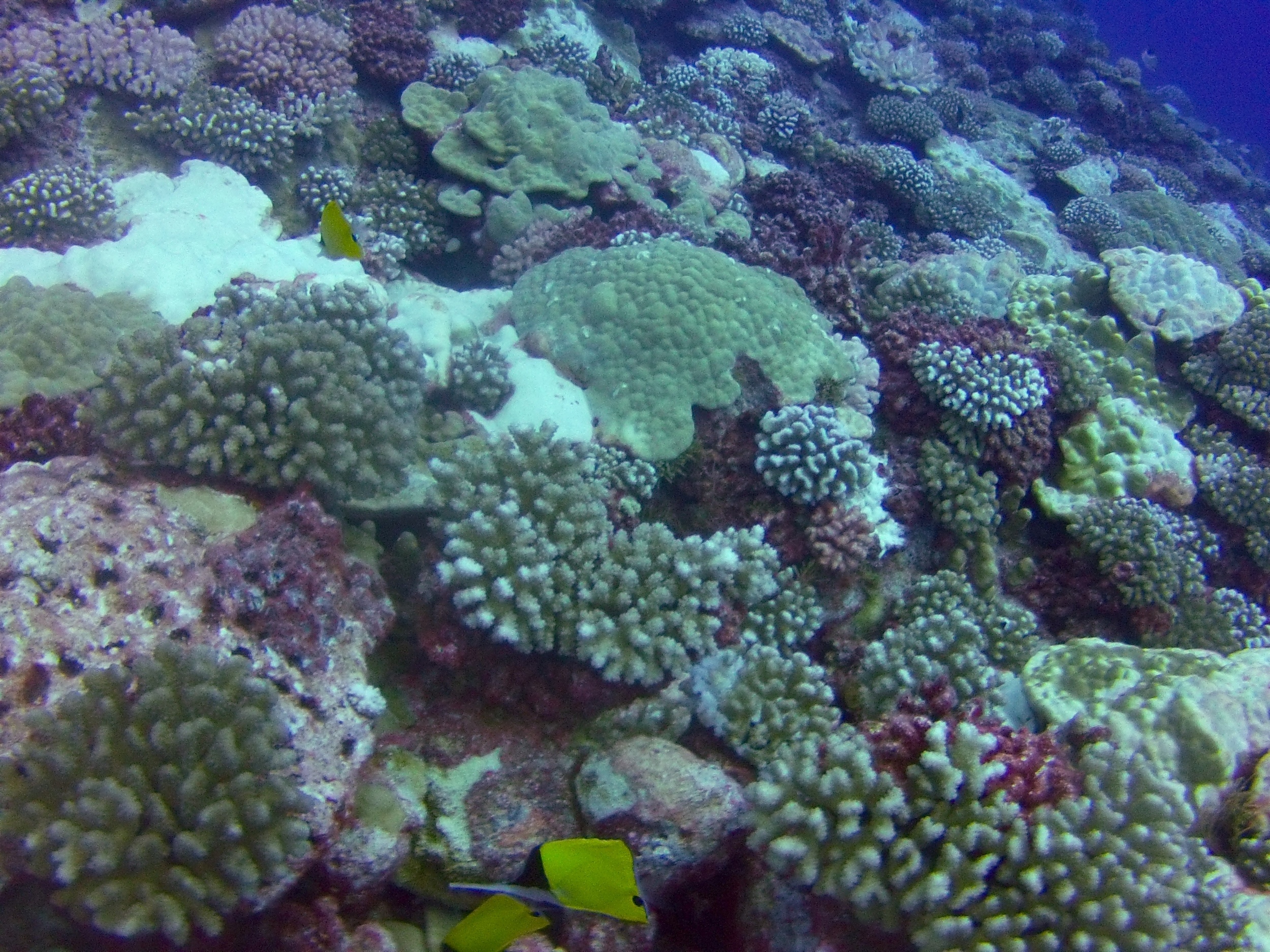

Bernard counts to 3 and we all fall back. My regulator stays in my mouth. The strap of my googles pushes up, but otherwise they stay on. Things are starting better already. I float on my own andcontrol my own descent. I release pressure from my ears. Balanced now, I am able to float along in the current on my own. We see colorful coral that drops off vertically into 10,000 feet of depth. Crystal says the coral is bleached from the warm water of El Nino, but I haven’t ever seen anything like it, so I’m easy to please. A few colorful fish swim around, and our group sees one shark, but I miss it. I enjoy just being underwater. I remember why I wanted to get certified, and I recommit to diving more.

By the time we finish, I am happy again. I went from out of my comfort zone to back in a matter of hours. I was embarrassed about needing as much help as I did on the first dive, but I was grateful to Martine for being there to literally hold my hand. It’s ok. Small failures will lead to more success if I learn from them. I realize we should dive more often to keep our skills fresh. I also realized it is a good thing we couldn’t fit tanks and gear on Sonrisa. We shouldn’t be trying to do this alone. At very least, the lessons from this failure will probably keep me alive and kicking a little longer.