The alarm on my wrist watch rings, and I drag my eyelids open. I’m pinned between the laundry bag stuffed full with our dirty clothes and Andrew’s bony knees. This is good, though, because we are parked a bit on a slant and before I shoved the laundry bag to my left, I found myself tucked into the footwell of the sliding van door. My right hip is aching a bit from laying on the plywood board beneath the van's ever flattening mattress. As my eye lids get heavy and try to close against my will, I try to engage my body to shuffle from my right side to my left. Everything is so tired that the best I can do is roll to my back. “Maybe I’ll make it to the left side later.” I think, and relax back happily as all my tired muscles settle into place.

We were both looking forward to the Mount Cook area more than any other part of New Zealand. We caught glimpses of it from the West Coast, and we could see the magical alpine peak stretched up to the blue sky, covered in glaciers and snow, even mid-summer. It just teased us, pushing us along on our drive and making sure we didn’t linger too long anywhere.

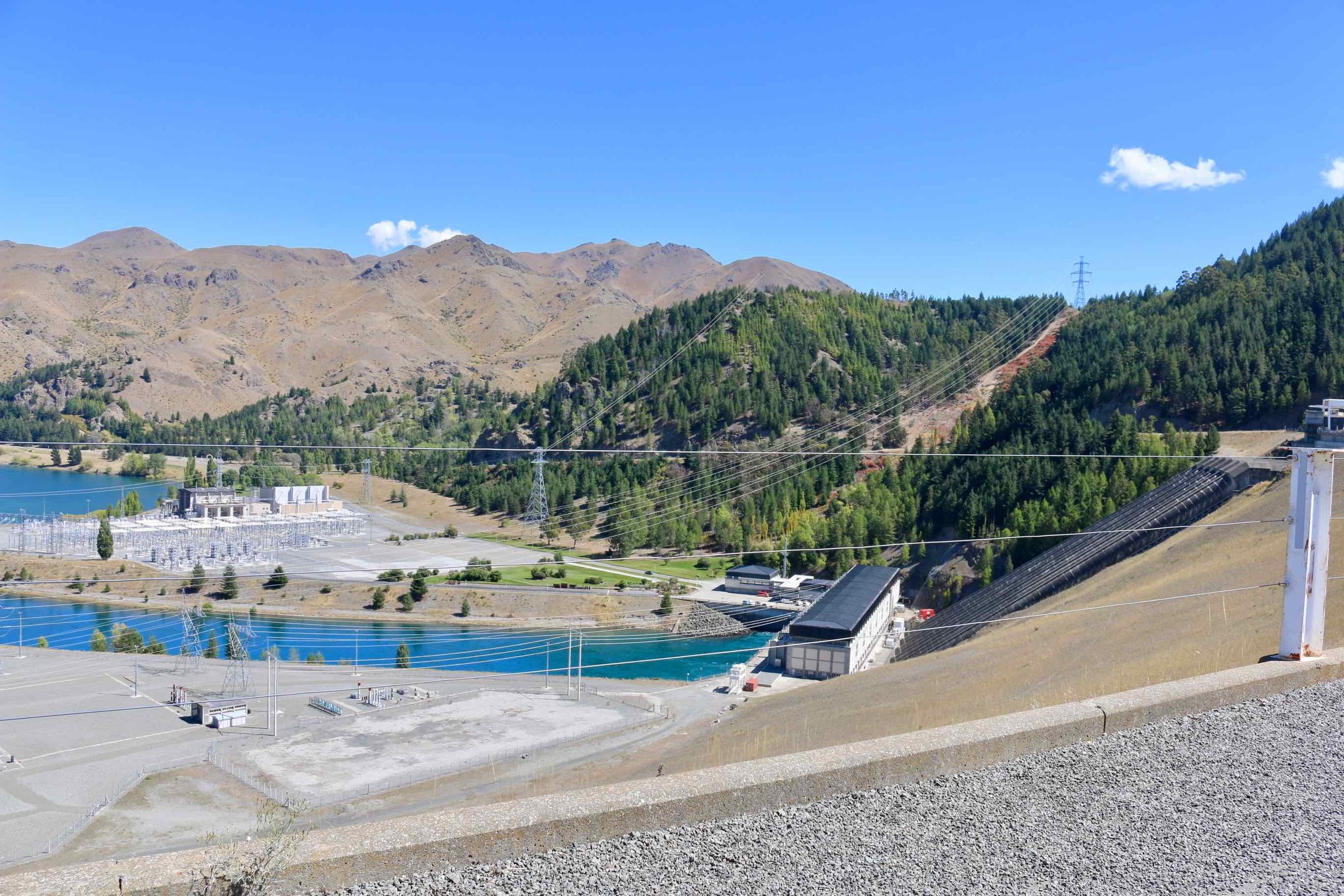

Once we left Oamaru, we headed over the Mount Cook. We passed a string of eight hydro electric dams built along a river. Many remote campsites were located on the back side of the man-made lakes, tempting us to stop and lounge in the sun. But, we kept going.

We stopped to buy some smoked salmon at a salmon farm and eat a salmon pie. Then, we arrived in the valley below Mount Cook, Mount Sefton, and Mount Tasman. As we took the turnoff to the Mt. Cook road, we quickly came upon a lookout over a beautiful lake. A little explanation of what causes this unique color of blue. Glaciers grind the rock to an extremely fine “glacial flour”, this mixes with the melt water of the glacier to form “glacial milk” lakes and rivers below the glacier. Initially the water is a muddy grey color, and tastes like mud if any of you were curious like I was. But as the water makes its way down hill and slows down, much of the mud settles out leaving only the extremely fine particles that reflect an amazing blue color unique to glacier water. There is no way that Andrew could pass up the opportunity to swim in this amazing lake, so we throw on our swim suits and make a hike down to the lake edge. The first foot of the water had been warmed by the sun and was tolerable so we swam and skipped rocks for as long as we could.

As we drive closer and closer to Mount Cook, the landscape remains perfectly flat. The glaciers and avalanches of the area filled up the valley with grit, gravel and rock leaving the ground level and allowing the mountains to jump straight up on either side. People pull over and unfold their camp chairs on the side of the road, just to enjoy the view. We would like to stop, but it is Friday and we know how these campsites can fill up. ONWARD!

Once we get to the campsite, we meet some new friends and pull out wine and cheese. We get the last parking spot just before the hiking trails start, so when you open Sister Mary Francis’s driver side slider, you get a perfect view.

Every now and then the mountain lets off a deep, long rumble, the sound of glacier ice and rock letting loose from its perch and migrating somewhere new.

Cascade of avalanche snow. MUCH BIGGER than it seems given the size of the mountains around it and the distance from my camera.

We hike a little trail and nestle ourselves in rocks to watch Mount Cook turn pink in the sunset.

The next morning, we choose the “easy trail” so we don’t wear our legs out on the hard trail and fail to hike anywhere else. So, we hike the Hooker Valley. Three crazy suspension bridges over milky glacier rivers and a gentle hike take you to a glacier lake filled with floating ice bergs. Andrew takes one look at those ice bergs and decides he must have a chunk to chill his New Zealand Doublewood Whisky waiting for him back at the car. He also has not met a glacier lake that won't swim, so he wades into the water.

This lake is cold. The bite of water chilled by the world’s biggest ice cubes is serious business. Andrew gets out to the point where it is deep enough to dunk, leans down then submerges his whole head. He stays down longer than I ever would have, then stands up to walk out. “I can’t feel my legs!” He wobbles around, trying to pick his way over the sharp and craggy rocks lining the lake bed, complaining he can’t feel his feet or legs. Per usual, I start envisioning what I will do if I have to go drag him out. It doesn’t look very deep, so if he goes down face first, I can roll him over and float him face up I think.

(He makes this look pleasant, no?)

Finally, he is on shore, bright red feet soaking up the sun. He is disappointed that he couldn’t swim out to get ice for his whiskey. “Your turn!” He says. “You have always regretted not swimming in the glacier lake in Montana.” I scowl for a minute and think back. Did I regret that? I don’t remember regretting that.

“No, I didn’t.” I was perfectly happy to watch a knucklehead in his underwear dive into a lake filled with giant ice cubes. But, given this glacier lake was so shallow, I figured I would dip my feet in and see what it was all about. I walk out to my knees. At first it is not so bad, feels like laying your hand on the ice accumulated on the side of the freezer plates. But as I walk further, my legs start to tingle, pin pricks poke my feet, and then it all goes pretty numb. Brrr! I make Andrew shoot a picture then I start hiking out. The rocks under my feet are wobbly and sharp, but I can’t really feel them. They move under each of my steps making me off balance. I will be very annoyed if I fall over. I make it to the shore and warm my feet up in the sun, too. This feels as good as anything I have ever felt.

Look. There, I'm in. Brrrr.

Some hikers walk by and cheer Andrew, incredulous that he would swim in the cold water. “Don’t give him any more encouragement,” I think.

We wait along side the shore for a smaller ice chunk to get pushed our way from the current flowing through the lake and down the river. A gathering of hikers surrounds the ice cube about the size of a large cow. We all inspect it, touch it, take pictures. When everyone is ready to disburse, we stow away a chunk of ice in Andrew’s waterproof coat hoping it will last the hike down. I name it Cuebert — an obvious medley of iceCUBE and iceBERg. I whisper to Cuebert to hang on while we hike it the hour down to camp in the warmth and the heat.

We feel like we are smuggling a rare bird out of its natural habitat, but really, Cuebert wasn’t long for this world anyway. I imagine him breaking off from his big ice berg family to leave home and make something of himself: ice for delicious whiskey.

He makes it home. And he is delicious. I wonder how old Cuebert is. 100 years? 1000 years? 100,000 years? “Isn’t there an X-Files about this?” Andrew says. Yes, the first one is all about everyone getting some crazy parasite or something drilling in Antarctic Ice. But Cuebert wouldn’t do that to us, and in any case the whiskey will kill any ancient parasite, right? Or maybe this ancient parasite will improve memory function.

We enjoy another dinner with our camp-neighbors and great conversation. More new friends! Tomorrow, we plan to hike to the top of the nearest peak for a better look at the ice, avalanches and craggy rocks. So, we head to bed near cruiser’s midnight (9:00 p.m.) and fall asleep to mountain rumbles. “When I am senile,” Andrew says “remind me about the rumbling this mountain makes.”