We arrive in Balibo and disembark the truck I’m now calling “Little America.” The village is built around one open common space square with a statue in the middle. An older Timorese woman walks down a picturesque hillside, her head wrapped in a skirt of fabric the traditional way. The only sound in town are birds, chirping from inside hiding spaces in the shade, and the lazy chewing of a cow pulling at grass.

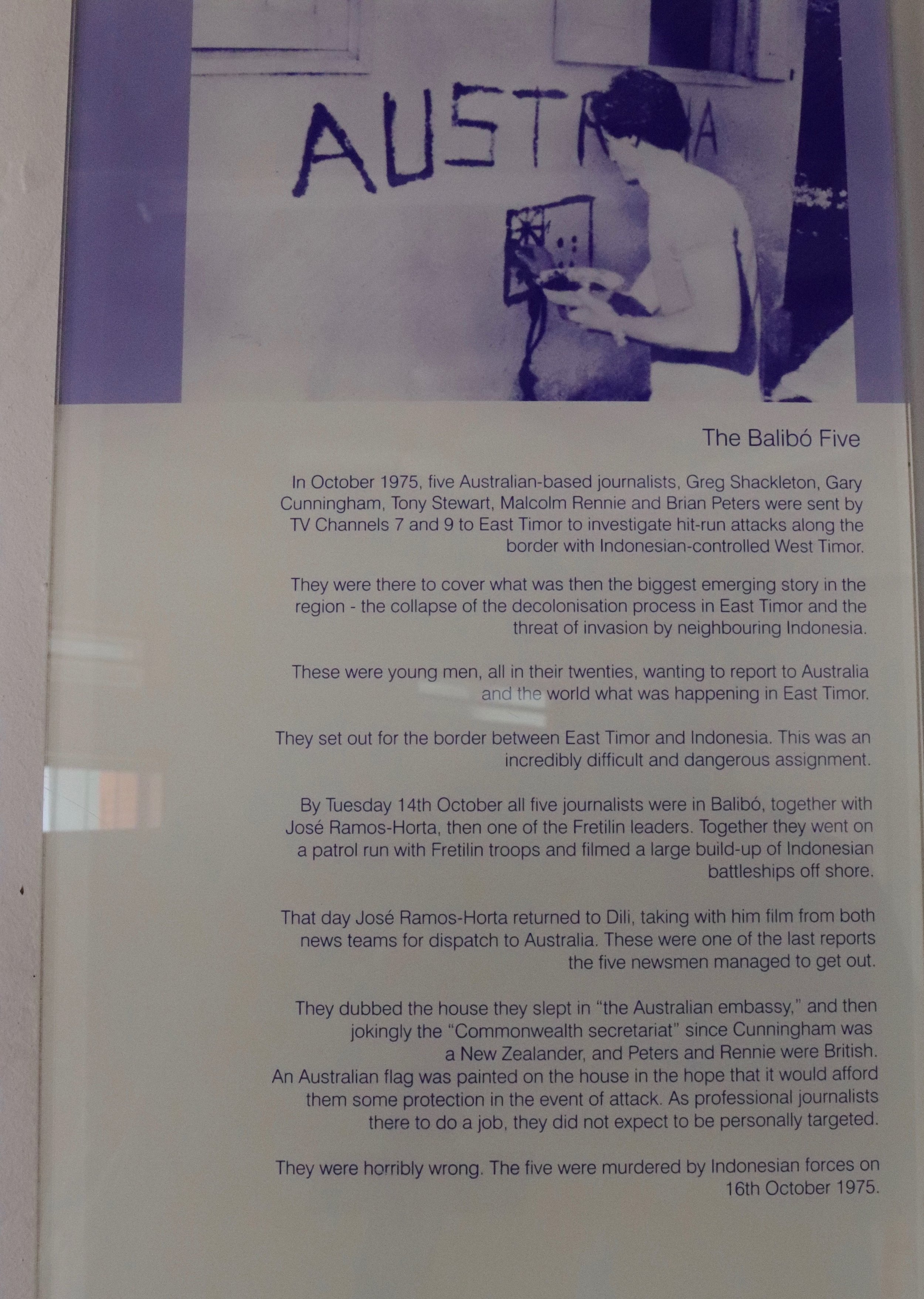

A small white building stands opposite the parking area, a red, spray painted flag states “AUSTRALIA” on the wall. It’s nothing but a crude outline, art created in a rush, the sole purpose a plea for safety. The original was painted in 1975, by a group of journalists from Australia. They had heard civil war was starting as the colonial power of Portugal relinquished control of the territory now known as Timor Leste. They arrived with cameras, intending to bear witness to the world of whatever happened next. Tongue in cheek, they called the little house the “Australian Embassy”. They painted the sign on the wall, as if to say to the invading forces “Don’t kill us, we are Australians.”

Really, the conflict started as far back as 1556 when Dominican Friars from Portugal established an outpost in a Timorese village called Lifau. In the 1600s, Portugal invaded the island, established a trading post, and began mining it for sandalwood and spices. In 1749, the Dutch and the Portuguese battled over the island and it was split between the two colonial powers: West was taken by the Dutch, East Portuguese. This laid the table for three more centuries of struggle.

The Timorese long desired to be free of their colonial control. In 1910, the Timorese organized a rebellion, only to be squashed a few years later by Portuguese troops rounded up from other Portuguese colonies in Mozambique and Macau. World War II came to Timor’s shores with Australian and Dutch troops taking up occupancy to fight Japan. Japan invaded anyway, and 60,000 Timorese were killed in 1942 alone, caught in the middle of fighting between Japan, Australia, and the Dutch. At the end of World War II, the Dutch relinquished its portion of the island (West Timor) to Indonesia. Portugal remained in control of the eastern portion of the island until 1975.

In 1975, Portugal’s Authoritarian Regime was overthrown by a military coup-turned civil resistance half a world away from East Timor, in Portugal. Democracy began in Portugal, and as a result, Portugal began withdrawing from its African colonies. This led Timor Leste to declare independence, and it wasn’t long before Indonesia - its neighbor in control of West Timor - marched over the border to invade. Portugal, occupied by its own problems did nothing to rebut Timor Leste’s declaration of independence or protect it from encroaching Indonesian neighbors.

Around this same time, Indonesia had been purchasing weapons and arms from the United States, for the stated purpose of defending against the spread of communism. Stockpiled with munitions, airplanes, war ships, and a well formed military, Indonesia invaded Timor. The four Australian journalists were killed, their bodies later found in a building across the way, marked by scalps.

This was only the start. The Indonesian Military coordinated a large scale attack, not just through villages near the Indonesian border like Balibo, but also by sea and air into the Capital City, Dili. They sent in brigade after brigade, to kill all the men and boys they could find. The unarmed Timorese fled, running into the steep, jungled mountain side for safety. 100,000 Timorese died in this initial invasion.

“Durva remembers when it happened.” Bill tells us. Durva nodding along side him. “She and her family had to flee into the mountains.”

The Australian government was the first to officially recognize Indonesia’s control over Timor Leste. During negotiations with Indonesia over a seabed boundary between the two countries, the Australian Prime Minister agreed to order the seizure of a two way radio link between East Timor and Australia being operated by Timorese supporters in Darwin. Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser instructed the Australian Telecom outpost radio service to cease picking up and passing on Timor Leste’s messages. “It is not in the national interest of Australia to intervene in any conflict of East Timor.” Australia, the US and the world generally were not sympathetic to helping a people characterized as “communist.” The Darwin radio outpost was the only connection Timor Leste had to the outside world. Cut off from communication and without weaponry, the Timorese were left to their own devices.

From 1975 until the late 1990s, Indonesia remained in control. Indonesia erected this statue in Bilibo, “commemorating” Timor Leste’s freedom from the bonds of colonialism and declaring Timor Leste to be Indonesia’s 27th District. But, many of the Timorese no more wanted to be Indonesia’s 27th District than they wanted to be a Portuguese Colony. One group formed a Resistance Movement; from the Indonesian perspective, they were considered the rebels.

“You never knew when someone would be taken away, never to be seen again.” Durva tells us. “the military would come into our homes, take our fathers, uncles, brothers. If they were accused of being ‘rebels’ against Indonesian control, they would be taken away and we’d never see them again. I lost one my uncles this way. We struggled to farm enough food, drought became a factor, everyone was starving.” 200,000 Timorese were killed during this timeframe as a result of repression and famine.

In 1991, a group of pro-Independence university students held a demonstration against Indonesian occupation. Their plan was to march from the center of the village to the village cemetery, where they would protest the political deaths and disappearances of their loved ones. Early in the march, a brief confrontation occurred between Indonesian troops and protesters. A number of protesters and one Indonesian Major were stabbed. Later, the surviving Timorese claimed the Major attacked the group of protestors including a girl carrying a flag of Timor Leste. The procession continued to the local cemetery, despite the scuffle. Here, a army of Indonesian soldiers and police arrived. They opened fire and killed more than 200 unarmed Timorese students.

At some point, a satellite phone was smuggled in to Timor Leste, allowing the Resistance Leader, Xanana Gusmo, to communicate again with the outside world. The Timorese were able to get word out that they are starving to death and trying to fight oppressors all on their own. They were able to confirm Timor Leste is not communist, and therefore not a threat to democracy. The world started to take notice; pressure started to mount against Indonesia to leave the Timorese be.

In 1999, the UN facilitated talks between Portugal and Indonesia, leading to a referendum vote regarding independence in Timor Leste. 78% of the Timorese voted in favor of Independence. Upon receiving this news, once again, anti-independence groups and Indonesian military went on a rampage, killing Timorese, setting whole villages afire, and destroying the Timorese infrastructure wherever they could. Anti-Indonesian groups in Timor responded with their own violence against anyone seen as friendly to Indonesia. Australian led International peace keeping coalitions came in to stop the violence. From 1999 - 2012, UN peace keeping forces occupied Timor Leste to prevent a reoccurrence of violence and to allow Timor Leste time and space to establish its new nation. Australia was rewarded for it peace keeping leadership with a contract allowing it to mine various Timor Leste resources including oil.

“I was stationed here in Balibo.” Bill explained, “part of the US contribution to the UN Peacekeepers.”

To put all of this in perspective: Timor Leste’s population in 1975 before the invasion was 600,000 people. Between the 100,000 person loss in the initial invasion, and the 200,000 people lost during the years of oppression between 1975 and 1999, half of Timor Leste’s population was extinguished by the conflict.

I wonder how these years of violence have impacted the personality of the culture. My mind flips through slides of my little observations of this country. The people running and working out, the charred buildings, the razor and barbed wire, the shy demeanor, 20 year old Nithon’s bright hopes and optimism: how many of these are echoes of a people fighting to be independent, scrapping to survive?

In random side stories, Durva speaks of her Indonesian friends, trips to Kupang, or Bali. It surprises me a little bit. “It seems like the Timorese people are still friends with Indonesians?” I ask.

“Oh yes,” Durva says, “The Indonesian Military and the Indonesian people are two different things. The people are all just like us. In fact, for a time, my family fled to Kupang to escape the violence here.” Kupang is a city at the far West end of Timor Island, technically West Timor, Indonesia.

“You fled to Indonesia?” I said, flummoxed by this added fact. “And they kept you safe there?"

Durva nods. “Sure.”

I marvel, to think of the innocence and resilience retained in the hearts of the Timorese that would allow them to forgive and enjoy the company of their Indonesian neighbors. Equally, I wonder at how the Indonesian people’s hearts could be inoculated against harboring hate for the Timorese, as their government likely told them to do. It would be naive to think that this violence was one sided; I’m sure Indonesian young men died in the conflict, too.

As we turn to head back to Dili, we swing past the Indonesia/Timorese land border. It’s peaceful, sunny, vehicles drive back and forth through the division. A dividing line in space between nations, a dividing line in time between war and peace.