Captain Andrew getting more grey hair by the minute while studying the weather.

With Steel Sapphire’s IridiumGo on the fritz, we all wondered what to do next. Pete and Jen couldn’t possibly go to sea without weather prediction, not on this route. And it would not be the seafarer-like thing to do to leave a ship behind. Calls were made, repairs attempted, options considered, but the bottom line was, Steel Sapphire's IridiumGo could not be repaired, and certaintly there were none to replace it in Tanzania.

Option 1? Fly out, buy a new IridiumGo somewhere else and bring it back, certainly missing this weather window, and likely more to come. From where would one fly out? Where would one fly into? What Covid quarantine requirements would exist given they would be flying out of Tanzania where Covid “doesn’t exist.” And who would take care of Frenemy Coco if Erie Spirit and the Oddgodfreys sailed on?

Option 2? No one had to broach the topic, we all knew there was no other way. The “Three Amigos” would sail close together while Mark and Andrew would provide weather reporting, routing advice, and email communication relay to Steel Sapphire via VHF or SSB Radio.

We cast off on Saturday morning, tossing a nip of rum to Neptune in our wake. Steel Sapphire took the lead, and Erie Spirit trailed just behind us. The wind was dead calm, and the boabab trees stood in a row as we slipped out from the embrace of Mikandani Bay. My engine chugged along, irritating the cat, but pushing us out to sea.

We knew the start of this passage would lack wind. Our strategy was to get out early and make as much headway South as we could before the inevitable Southerly storm brewed up. The plan, then, was to decide: should we try to sail through it? Or should we divert to hide behind an island off the coast of Mozambique until the storm passed? These decisions would be made in the moment, knowing as anyone does, that weather forecasts change and shapeshift like ripples on water.

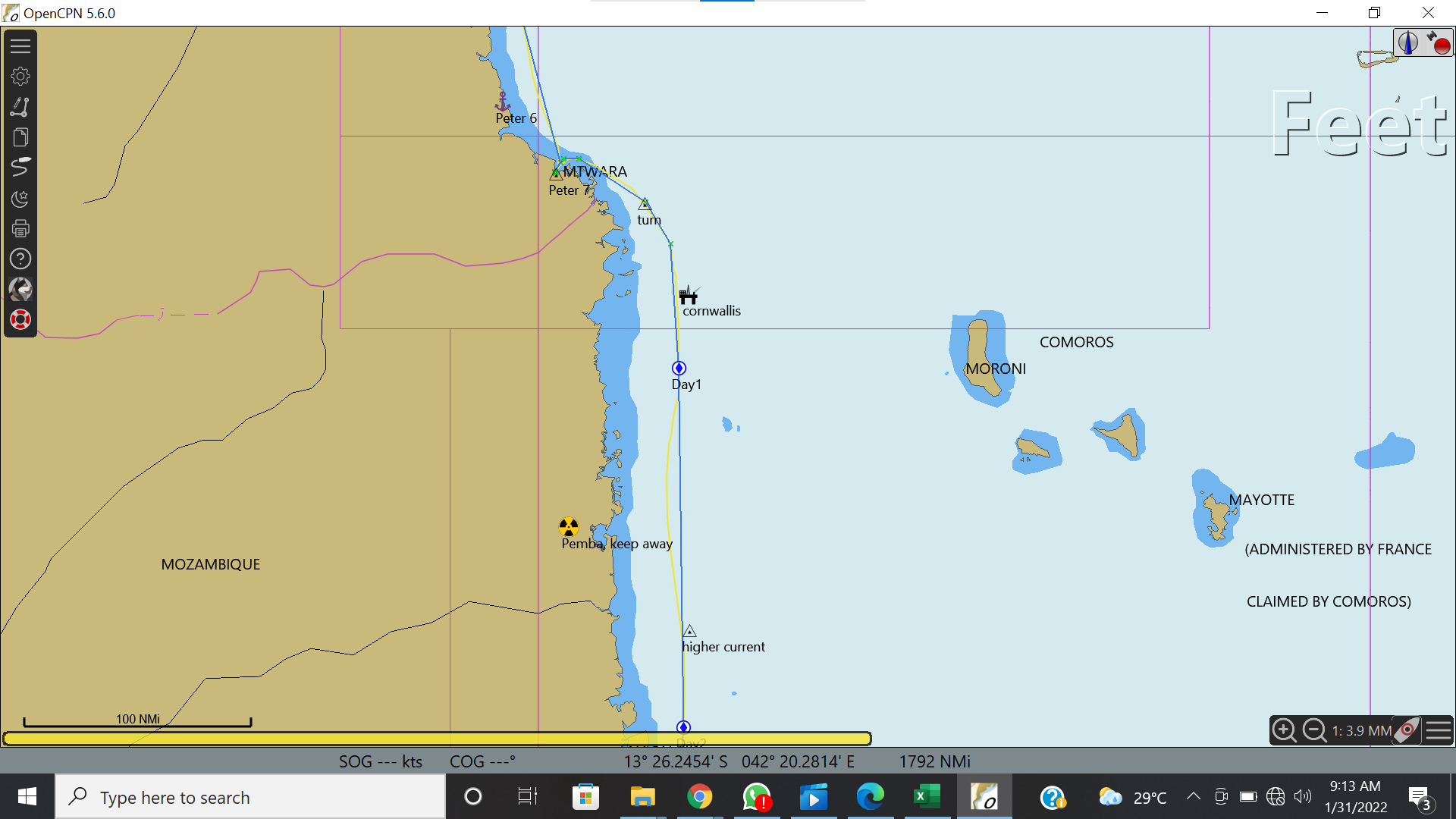

Charts for Day 1: Our planned route is the green line, our route as it occurred is cast in yellow.

To assist with interpreting weather-reports as good as reading tea leaves, we connected with South Africa’s ever famous, fully volunteer weather router - Des Cason. He was to email us input based on his 40 years of experience sailing the “Wild Coast” of South Africa and the Mozambique Channel as a recreational sailor and professional delivery skipper.

It’s extremely difficult to get across to yachties how treacherous this channel and the South Africa Coast is. A number of yachties who thought its just another piece of ocean have some lingering nightmares.

To have unreasonable ambitions on a stretch of ocean which you don’t know is looking for trouble.

It’s never a relaxed trip as you are constantly on the clock but providing the weather plays the game it usually is a bit of an anti climax. Only the smart asses who think they know the coast come short.

Des is an Old Salt who rarely minces words. He had already attempted to dissuade us from our last anchorage at Mafia island, describing it as “a place that lives up to its name” with an anchorage that leaves much to be desired. But of course, sailors are wily and quite often we decide to go our own course despite his better advice (Whalesharks!). Having gone to sea many times himself, he knows we might listen to him, we might not, and so he ends most his emails with “…but it’s Skipper’s choice.”

Weather routers are great sounding boards, but the fact remains that they are usually installed firmly on land and they aren’t sailing this boat, in this sea, with this crew. A good weather router knows that and doesn’t get bent out of shape when Captains take an alternate course. This passage was to be no different. Des would weigh in, give his input, and then my Captain would make real time decisions with the information he had available as we go. When Steelie lost her IridiumGo, suddenly Andrew and Mark had to take on a dual positions as Captains for me (Andrew) and Erie Spirit (Mark), but also as weather routers for Steelie.

“Oh boy,” I whisper to Leslie. “How’s this going to go?”

Leslie winces and shrugs. “I’m sure it will be fine!” she says. “If there is one thing we can all rely on, it is for Andrew to do whatever Andrew thinks is best.” But we both knew it would be an added layer of stress for him on a passage we knew had the potential to be the most difficult of our entire circumnavigation.

My engine chugged away for the first six hours, irritating Katherine Hepburn and sending her, scowling, to the bow of the boat. There, she negotiated quarters with the ghost of my former ship cat “Nubicat” who lived with me when I was owned by John and Sylvia. I was relieved when Katherine Hepburn climbed into the cubbyhole that used to be Nubicat’s favorite. It is definitely more comfortable than her usual spot on the bathroom shelf, and very secure.

Angry Cat, at the front doorstep of her Cat-Cubby.

As a sailboat, these passages do make me nervous, too. I take my job very seriously; I am responsible to get them safely from port to port. I rarely question whether I can handle whatever conditions the sea throws at me. Andrew keeps me so ship-shape, I know I’m ready for practically anything. I worry about what might happen to my crew. But there are things out of my control: what if one of them falls overboard? What if someone gets sick? And, most terrifying of all, what if we get into nasty weather and they decide to abandon me? There are countless stories of sailors getting scared in storms, abandoning their boats to enter the liferaft, only to have their sailboat wash up in tact and safely on shore while those sailors are never to be seen again. This is pretty much worst case scenario for me. I hate the whole idea. If I had opposable thumbs, I’d just tie everyone to the mast so they couldn’t escape. But, I’d rather just avoid the whole affair. And so, even I rely on Andrew to get the weather predition and routing decisions right.

No pressure, Captain.

That afternoon, we could see the gentle ripples sailors often call “cats paws” indicating a breath of wind was just beginning. “We can sail,” Leslie says to Andrew. “Let’s hoist the Code Zero.”

“Nawoooo, it’s still too light to hold.”

“No, it’s good! We can sail!” Leslie insisted.

“It’s still too far upwind. It needs to clock around.”

“No, no! We can do it!”

They debated this question long enough that the wind built to a light 5-8 knot breeze, and by the time Andrew agreed to try the Code Zero, we had just enough wind to hold. My crew hoisted the main sail, unsocked the Code Zero, and under the evening light my sail glowed golden. As Leslie pulls the choke to cease my rumbly engine, the peaceful gurlge of water passed my hull as I cut the surface. Katherine Hepburn ventures out of her cubby, purring and happy to finally be at sail.

Once the wind increased to 7-10 knots, we were flying! White foam was rolling off my bow. Wheeehewwww!” It was easy at this time to forget the challenges that lay ahead of us. If the wave and wind state could continue like this for the whole route...it would be the best sail ever! The moon rise was spectacular that night. It presented itself first as a big orange ball at the horizon, then transforming to a white-silver disc as it made it’s rise into the sky. A trail of glowing silver light glinted across every ripple from the horizon and to my hull. It couldn’t have been more beautiful.

Over the first three days, the wind built and died repeatedly, came from in front of us, the side, and behind us. We used every sail configuration I had. Andrew and Leslie were having fun. It felt like the “Good Ole Days” on Lake Mead, attending to sails, hoisting the spinnaker, dousing the spinnaker, trimming everything just so to get as much speed from me as they could. Our goal was to go fast to make it to a certain waypoint at a certain time, before the scheduled rough weather was to arrive. And, we were going quite fast! We had caught the Mozambique current running Southward and the ocean pulled me along on a conveyor belt populated by schools of dolphins who would sing and squeak all day and all night. My inhabitants could hear their voices through my hull while dozing into their off-watch sleep.

The VHF Radio chimed almost constantly with the song of weather prediction, current routing, or the general blathering that results from three friendly sailors sliding along in close proximity.

“Sonrisa, Erie Spirit, this is Steel Sapphire, Steel Sapphire, Steel Sapphire”...

“This is Sonrisa, go ahead.” ...

“Erie Spirit here.”

We may as well have been sitting at the pub sipping a brew, for the distinct lack of silence and solitude. Every day, at 10:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. an official meeting occurred. “The new weather report says this, changed like that. Our new route should be this, our arrival time should be that.” Pete would launch into questions, the poor guy trying to gauge the possibility of onward transit versus epic storm sailing “blind.”

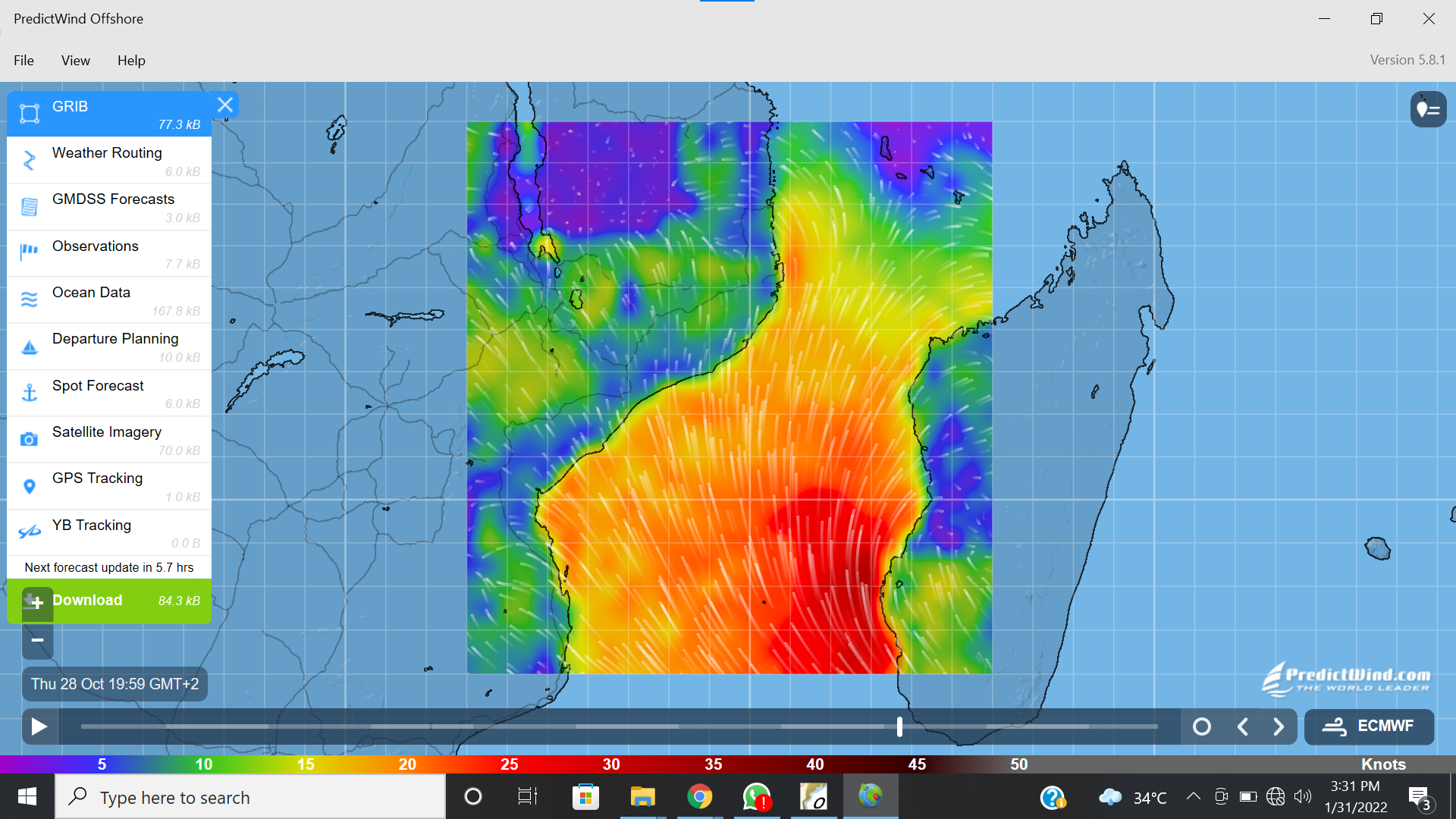

By noon on Day 4, we reached our decision point. The weather reports billowed with big splotches of orange and red across Andrew’s computer screen. Andrew squeezes the VHF Radio Microphone and states, “We probably need to bear off to hide at Fogo Island, Mozambique. A Southerly storm with winds forecasted anywhere between 22 and 30 knots is heading toward us.”

Pete, who sails a thirty-ton steel ship, does a few mental calculations - no doubt considering (at least a little bit) the months and weeks he has to sail from where we are today all the way to the UK to arrive at home in time for his mother’s 80th birthday. “I don’t think we need to bear off. Look, if you sail South into the middle of the channel, when the storm hits, we can bear away but keep sailing it and make a straight bee-line into Richard’s Bay.”

“It’s 22-30 knots over a Southbound current.”

“We’ve sailed 22 - 30 knots dozens of times in all the passage making we’ve done together!” Pete pointed out.

“Yes, but not with adverse current,” was Captain Andrew’s response. “Des reported messy conditions for some sailors ahead of us who had only 15 knots of wind against the Southbound current.”

“Baahhhhhhhhhh,” came the retort from a irracible Pete, “We all know Des is super cautious.”

The Captains finished their call without a decision being made, we still have a few hours until the point of no return. Andrew warms my crew’s dinner over the stove while Leslie keeps watch. I can tell his mind is spinning through options.

“Why take the chance?” Leslie says, when he nestles down into his cockpit beanbag.

“We all kind of pride ourselves on choosing boats that should be able to handle a blow,” Andrew said. “We probably could keep going.”

“Sonrisa can handle it if she must,” Leslie said, “but, she trusts you not to make her do that if you can avoid it. And, decisions like that are expensive even if they aren’t life and death. Rip a sail, and you’ll be shelling out an easy $1,000 to fix it.”

“Yeah...but it is only 30 knots,” Andrew said. “I don't want to have to deal with a shakedown in Mozambique if we can avoid it.” Mozambique has a reputation for officials who may or may not come out to the boat, demand money, take your passports and hold them ransom, or issue wholly unpredictable “fines” for anything they can think to fine you. This too, is an unpleasant reality about this sail Southward.

“If we were sailing alone, what would you do?” Leslie asks.

Andrew purses his lips, but doesn't answer.

The Radio call reconvenes after dinner, with Pete hailing again to discuss further thoughts. “I’ve fired off an email to Des. Let’s see what he has to say,” Andrew suggests.

Pete grumbles. “You know what Des is going to say.”

Indeed, Des has a history of cautious advice and respect for the risks on this Coast. Andrew did presume Des would respond with some encouragement pushing us into Fogo - at least until the email came back:

“To be quite candid, I was tempted to recommend you…get into the center channel”

“Ahhh come on, Des!” Andrew said, reading the email.

After 6 years at this lark, I’ve had very few recriminations from yachties for risky tactics, but there is always a first.

Unfortunately…it’s skipper’s call!

Andrew growls as he hails the group to report back.

“So what did Des say?” Pete’s voice crackled over the radio with hope for onward passage.

Andrew winces and reports. “…but I don’t think it’s the right decision for us.”

“Yeah, I’m not going down the middle of the channel,” Mark on Erie Spirit confirms.

There is a pause on the other side of the radio, and I can feel Andrew grinding his teeth. “I’m going to Fogo. You can go down the channel and I’ll guide you from the SSB, but I’m not going.”

This prospect couldn’t sit well with Steel Sapphire either. So far, we’d been sailing close enought to use our VHF Radios, with their simple line of sight relay. If we got too far apart, they would no longer work and we would have to move to the Single Side Band Radios which are just like Ham Radios for the marine industry. The SSB is a powerful tool, but it requires more skill and technique to get the frequencies on two radios to match well enough that the sound comes through clearly. Finding these frequencies require a user to consider the weather, position of the sun, relative distance between radios, and a whole host of other factors that sometimes boil down to luck. What if they couldn't make the connection and Pete was left with no communications and no weather prediction at all?

Reluctantly, Pete agrees to follow Erie Spirit and me into the Fogo Anchorage. We make our turn West at 18:00h (6 p.m.), the wind meter started its upward climb until we were reefed down tight and Leslie was white knuckling her night watch.

Diverting course to hide behind Fogo.