This seems like an opportune moment to answer one of the most common questions we get when we say we want to sail around the world: "What about storms at sea?" Yes, this is something that must be considered. To prepare ourselves, we read many books, sailed in moderately high winds (up to 40 knots), and bought a well founded boat. Bad weather is not something we want to go out in by choice, so our best "practice" has been to launch our storm gear on a normal day to see how it works.

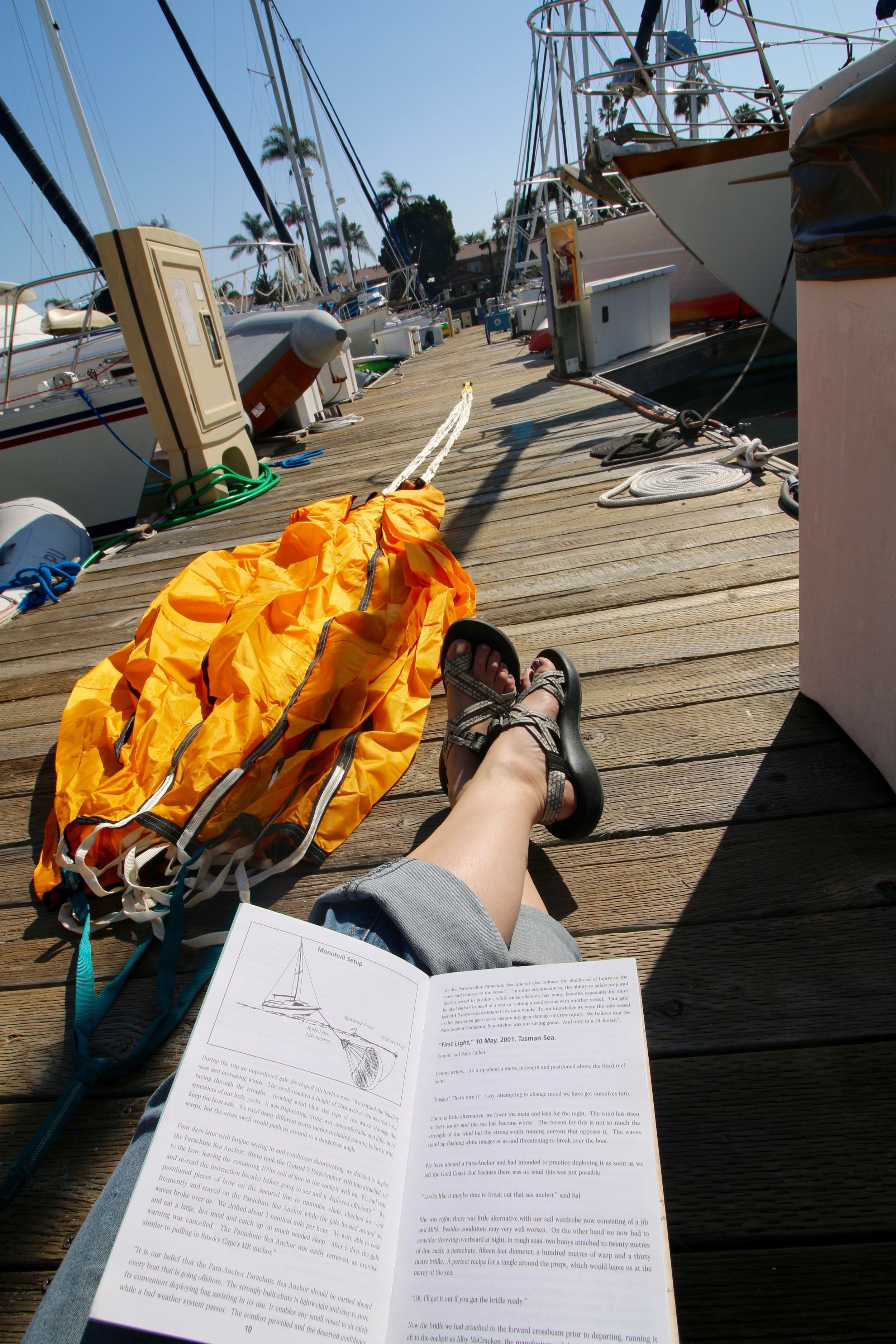

Before we left San Diego, I was tasked with inspecting and figuring out how to launch our storm gear. I wrestled the storm jib, the storm trysail, the a sea anchor, and the drouge out of the storage space beneath our aft bunk. I laid them out on the deck, in the calm sunshine of our marina slip in San Diego. I polished the metal parts to remove any rust or corrosion, and then inspected everything for cracks, broken wire, or other problems bound to create havoc in heavy weather conditions. Next, I did a "dry" run, launching the storm jib (a very small forward sail) and the storm trysail (a very small main sail) to see how it would go. As I slowly and awkwardly practiced attaching everything to the boat, I imagined what it might be like to crawl forward in my foul weather gear, slowly attach the storm jib one hank at a time, while being doused with waves over the bow. Rightfully, the prospect terrifies me. Nonetheless, short of putting ourselves out into bad weather on purpose to try it out, we are as prepared as possible.

Storm Tactic #1 Hunt for a Good Weather Window

Many people sail around the world and never encounter scary storms because they do not go out when/where storms are likely to occur. Sonrisa has sailed across the Pacific twice before, and none of her storm gear has ever been used. Our stop in Maupiti is a perfect example of hunting a good weather window. We could see a storm was coming our way, so instead of starting a five day passage, we found a chunk of land to hide behind. We will never be sailing in hurricane seasons/areas so the likelihood of experiencing a really strong storm is low. We watch the weather as best we can before starting a passage, and we wait until we have as good of a weather window as possible.

But, as you know, sometimes weather forecasts are wrong and sometimes, our passages are so long that we can't know what might pop up two weeks into a three week journey. While we are on passage, we still get forecasts for our area emailed over our SSB radio and we watch our radar. If we see a storm coming, and can do so, we will divert our course to skirt or avoid the storm. But, of course, sometimes a storm could be to big or too fast moving for us to divert course. In that case, we have a series of other tactics to deploy.

Storm Tactic #2 Reef The Sails and Alter Course

The first tactic at sea is to reef the sails. This means that we take the sails we normally use and tie them down to make them smaller. We have strong and solid roller furling, so our jib can be reefed just by rolling it up a little bit. The main sail has three reef points, with lines run back into the cockpit, so it can be shortened to three different sizes. Sonrisa is a solid boat with a great seaworthy design, so we anticipate this tactic will work up to 45 or 50 knots of wind. 35 knots is the highest we have experienced in her so far, and we were sailing happily along with no problems.

Once you have your sails shortened, there are three options to employ without using other crazy equipment: (1) We can "forereach", which means you keep sailing mostly up wind (against the wind) but at an angle so you don't go straight up and down the waves. (60 degrees off the wind, for you sailors out there) (2) We can "run off" which means we could turn around and sail down wind (the same direction the wind is blowing) until the storm lets up. Sailing downwind is more comfortable and less strain on the boat. (3) We can "hove-to", which means that you essentially set one sail to pull the boat right, one sail to pull the boat left, and you set your rudder so that the two sails balance each other out. Your boat will just stop, and if you have the right kind of hull design, you will point with your bow mostly into the waves and scooter along sideways very slowly. Sonrisa is very good at hoving-to. She stays balanced and scuttles sideways as smoothly as can be expected in crazy waves. This is a handy tactic to use when we want to wait in place or pull in a fish or manage some other deck work at sea. So, we have practiced hoving-to several times.

If things are still too crazy, it's time to replace our normal sails with even smaller sails: storm sails. After rolling up the normal jib, the storm jib wraps around the regular jib with strong bronze hank on clips. Leaving just a tiny handkerchief size sail to sail with. The main sail gets replaced with another tiny sail called a storm trysail. The storm trysail has its own track attached to the mast, next to the normal main sail's track. We would bring down the normal main sail and tie it down tightly. Then, we would take the storm trysail up on the track next door. With these two tiny sails up, we have the same options for sailing tactics discussed above, but less wind force being collected by the boat. The boat would slow down a bit, heel over less, and be more in control.

According to old salts who have done this before, if you do it right, these tactics can be used to get you through anything so long as you remain physically capable of steering and running the boat, especially forereaching.

After inspecting and polishing everything, I folded our sails carefully and labeled the corners so that I have the best chance of an *easy* launch while I am being tossed around in the waves and dark of night when this is most likely to occur.

Tactic #3: Slow Your Roll

If the boat is still going too fast, (mostly likely if you are trying to run-off downwind), you risk burying the bow of your boat in the bottom of a wave and flipping head over tail. So, we have a piece of gear called a Jordan Series Style Drogue. This is a giant rope with little parachute cups sewn on every foot or so. You throw this rope out the back of the boat and let it trail behind you. This will slow the boat down. This piece of equipment can also help you steer in normal conditions if something happens and you lose your rudder.

Tactic #4: The Float and Pray

Worst case scenario, if we want to stop the boat with the bow into the waves and the wind/waves are too strong to do it by hoving to, we have a Para-Tech sea anchor. This is a big parachute you throw overboard in the front side of the boat, it holds the boat in one place*, letting the waves move under the boat, rather than the boat move up and down the waves.

Suffice it to say, I expect everything to go to hell in a hand-basket at night. Things never go crazy in the light, when you can see what you are doing and easily launch your storm gear. If we get to the point that any of these tools are needed, it will not be easy going. Our preference will always be to keep the boat moving with the wind and waves, so storm sails are our first tactic to deploy. Getting tangled up in parachute lines, getting ropes wound around the prop, and fooling around on deck to try to launch the sea anchor are all things that we would prefer not to do if we don't have to.

In addition, we always sail offshore with lifejackets and harnesses even on calm days. While these are still an imperfect solution (we have read of problems with people suffocating in the inflated lifejacket and/or being dragged face down tethered next to the boat), they are one extra layer of defense before we are washed away at sea. We have foul weather gear to keep us as comfortable* as possible, and sea boots to help us keep our footing. When we move around on deck the mantra is "Move Slower" and "One hand for you, one hand for the boat."

Sail boats are actually rather strong; it is usually the human crew that are the weak link. Valiants (Sonrisa's boat type) are built to withstand any type of storm you throw at it. Her design configuration means she is unlikely to capsize, but if she does, she will pop back up in a matter of a few seconds. Everything on board is lashed down or put away such that if she does roll over, things will not fly around and create a dangerous projectile. For example, heavy and potentially explosive batteries contained in a box fiberglassed to the hull then strapped down with Spectra (rope that is stronger than steel).

There are countless circumstances where the humans on board break before the boat. People jump into their life raft thinking that they are just in too much trouble, and then their boat washes up ashore in tact, but unmanned weeks later. Or, people lock themselves down below and just keep their fingers crossed that the boat will not get cross-wise to the waves.

After reading my favorite book on sailing in storms, John Krestchmer Sailing a Serious Ocean: Sailboats, Storms, Stories and Lessons Learned From 30 Years at Sea, the one thing I am sure of is that if you end up in crappy weather, your job is to stay engaged with the boat and the weather. You try one tactic, and when it stops working, you try another tactic. You hang on, and you keep working to take care of the boat and yourself. You can't just phone it in, and you cannot let fear and panic get the best of you. Luckily, Sonrisa is equipped with a Comfort Owl (and a small prescription for Xanax) to help us weather a storm.