On the outside world, Andrew and I are busy making new friends. Upon our arrival in Kumai, a man stops by in a long canoe with his wife and little girl to welcome us to the anchorage. He introduces himself as Madi, and he speaks excellent English. He invites us to explore his village once we return from our Orangutan tour. We accept, and make a plan to visit a few days hence. He arrives at Sonrisa’s hull one morning, ready to lead us through a small clearing in the palms. Grin and Andrew love this little estuary and over the course of the next week make lap after lap up and down while humming the theme from Indiana Jones. I peek out from under my umbrella, trying to get photos without getting my camera wet from rain.

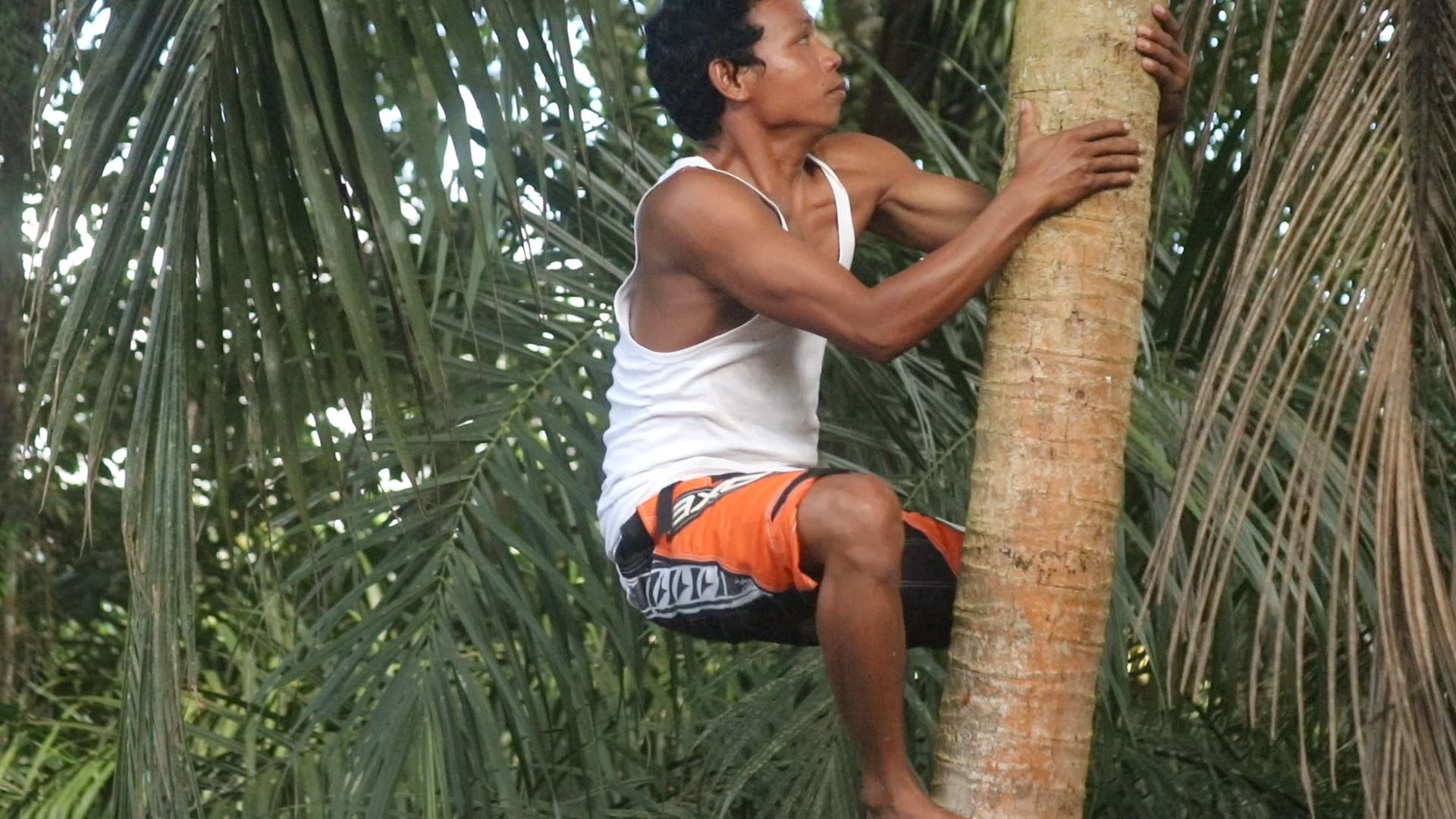

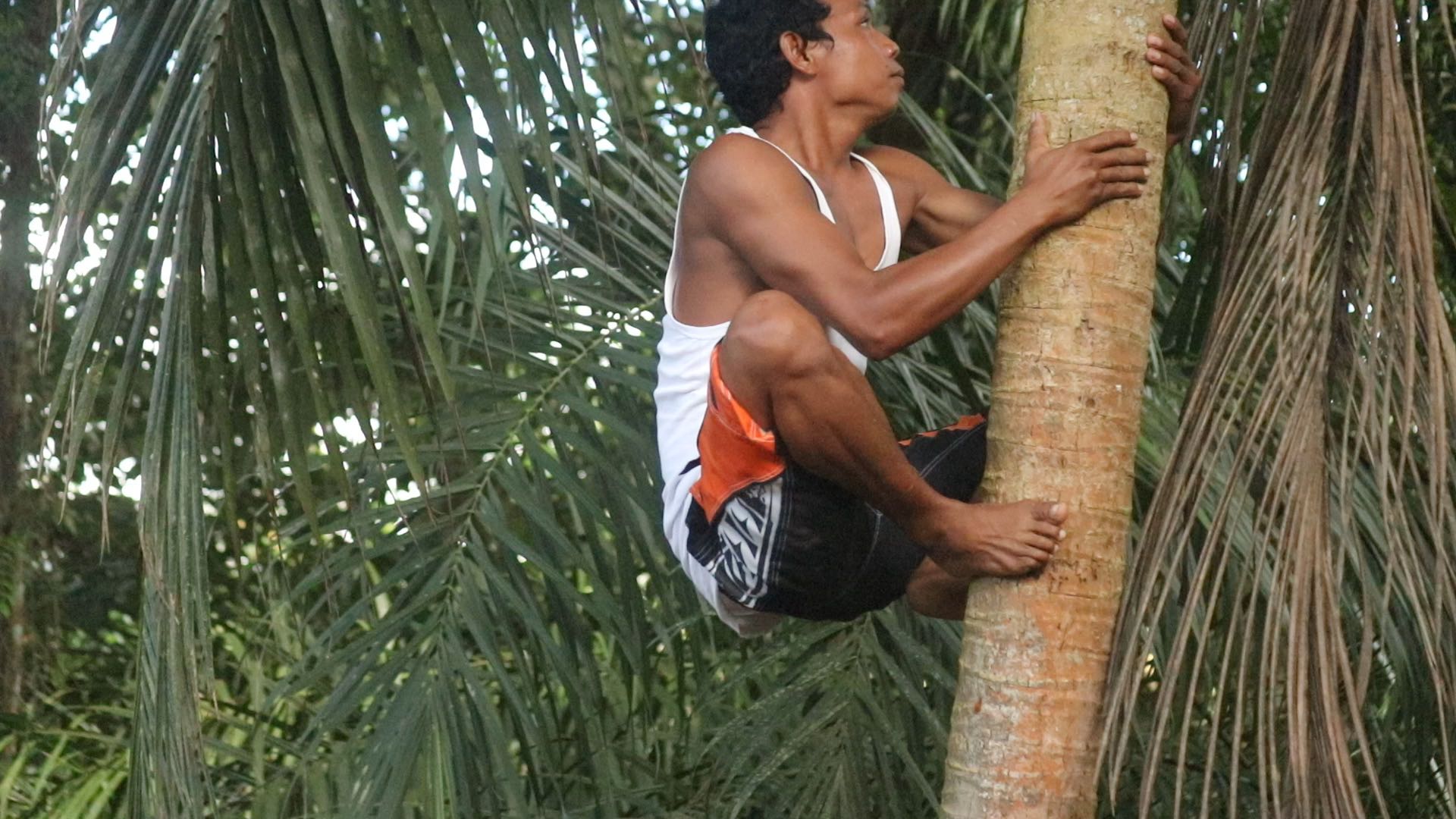

Madi takes us on a walk through the village. “This is my wife’s village,” he explains, “My family lives in Kumai proper.” Madi climbs a coconut tree and pulls down branches from three different varieties of Rombutan and coconuts literally as big as our heads.

In walking through the neighborhood, we happened upon a house painted with a big word “J-A-N-D-A” on it’s street-facing wall. “What does Janda mean?” I asked Madi.

“It means, ‘single mother’.” He says, matter of fact.

Wow, I think. What is this woman’s life like? Is her house painted with the word ‘Janda’ to make sure everyone reaches out to help? Or, more likely, is the label to ensure she is shunned, a daily reminder that she has children with no father to bring them up? I mull this unsettling fact of Indonesian culture while harboring a small seed of dread about the question we all know will be aimed toward me anytime now. It’s been an hour and a half, I’m surprised it hasn’t already come up.

Madi takes us to see his motorcycle repair shop and meet his family. Life as usual is proceeding at Madi’s house. His wife is cooking something for dinner, his twin daughters are playing in the yard, and his mother-in-law is waiting for her clients to arrive. Grandma smiles to see us visit and we speak what little Indonesian we can with her. A few moments later, a new mama and a tiny baby arrive from somewhere else in the neighborhood. Madi’s mother-in-law de-robes the baby, dips her thumbs in oil, then begins rubbing the little guy’s back in the same pattern as the Balinese massages we have experienced at various spas.

I’m fascinated. “What is she doing?” I ask Madi.

“She is the village midwife. She helps deliver babies when the mother can’t afford to go to a hospital, and she helps the babies with their health when they are just little.” Madi explains. The little guy in her arms starts wriggling and wailing. He doesn’t seem to like a massage as much as I do. “The babies cry now, but tonight he will sleep well.” Madi explains.

“Is he sick?” I ask.

“No, no, all babies need massages,” Madi tells me, as though this is obvious. “You don’t want their muscles and tendons to get rigid from stress do you?” When my face belies the fact that I had no idea babies were at such a risk Madi continues. “Babies can see all sorts of ghosts, you know. Sometimes it scares them and makes them tense. They need a massage so they can relax. It’s stressful to be a baby!”

“Hey, where are your babies?” Madi asks me.

I knew it was just a matter of time. “No babies,” I tell him. He looks to Andrew who shrugs his shoulders, the palms of both hands face up, and says “No babies.”

Madi can hardly believe this, and soon the information is passed around the circle to his wife, mother-in-law, the woman whose baby is receiving a massage, and no doubt six ladies down the street through some sort of Indonesian “no-baby” mental telepathy.

“Why no babies?”

I give him my honest, but not entirely honest answer, “I don’t know!” The group simultaneously shakes their heads and become very sad for me. Then, I feel guilty for not explaining the whole truth. Physiologically, I know exactly why I have no babies (thank you, Proctor & Gamble); it’s the other side of the coin that puzzles me. The desire has not arisen, but I do not know why.

In theory, in my homeland this sort of thing is “no one’s business,” but in Indonesia, everything is everyone’s business. The answer “Nonya Business” simply will not fly, and would only serve to alienate an otherwise warm and wonderful set of people.** And, marriage and motherhood is where a woman fits into this society; she may have other projects, own businesses, cook, keep the house, build her life with her husband and extended family, but what happens to a woman who does not have babies? As we learned with Aladdin in Maumere, she can be traded back to her father, dowry repaid. Apparently, there are repercussions for women who have babies but no husband, too. For this reason, I feel a sense of commonality with “Janda,” we are both women playing our roles differently than we were assigned to play. Is it wrong of me to omit the fact that at least to date we have chosen not to build our family? I feel dishonest, uncertain, and like I’m abandoning “Janda” to be alone in her life situation outside the norm. Am I taking ill advantage of sympathy from these friends who think Andrew and I must be trying so hard for twelve years of marriage, all to no avail? Or am I saving them from the discomfort of discovering we are Odd-Godfreys. Like other Indonesian friends have said to me: "Maybe tomorrow."

At this point, my internal dialogue has wandered far away from Madi’s Family Shade Hut through a maze of all these questions when Andrew comes through for me and distracts all of us with admiration for Madi’s brother in law’s machete tied around his hip. “Where do you get a machete like this?” Andrew asks.

“He made it!” Madi explains. “Only special men are allowed to make knives.” Madi’s brother in law hands it to Andrew who turns it over appraisingly. Andrew’s interest in the machete grows until soon, he’s acquired the knife for $15.00 US and Madi has set a plan for tomorrow’s field trip: a road tour of awesome knives. Madi’s brother also gives me a gift of two grass woven bracelets and a shark carved from a coconut shell.

“Thank you!” I say, “Terima Kaseih!”

“No, say Skakalongkong. It is Madurese for ‘thank you.’”

This confuses me quite a lot because “Skakalongkong” is very difficult to say and we are not on the island of Madura. Andrew and I repeatedly try to figure out how to remember and say this word, an exercise at which Madi’s family laughs and laughs. Much collective joy is gained in this small exercise as the sun drops below the lowest palm frond. We wave goodbye and rush back to where Grin awaits, to race down the narrow estuary river before we are trapped in the jungle with the tide falling and the sun setting.

** P.S. I recently asked one of my Indonesian friends what he might say if someone asked him a question about a topic he would like to keep private. He tipped his head to the side and furrowed his brow, as if he'd never contemplated the possibility. "Me? Private? Oh, I would never do that." And so I wonder: is it true he would never keep anything private? Or is he demonstrating the tactic he would use if someone asked him about something he wishes to keep private?

P.P.S. I searched the translation for "Janda" and learned the word includes a single mother, a woman whose husband has died and who has not remarried, or a woman who is divorced.