“Meditation brings wisdom; lack of meditation leaves ignorance.” The Buddha.

The train station is as I imagined it. Silver train cars line up with their toes against the yellow line, waiting for their passengers to embark. Glossy floors reflect the shadows of people bustling around, readying their backpacks and their tickets. A string of clocks tell the times of major cities across the world. A monk in an orange robe meditates along the beads of his mala as he waits for his destination to be called.

Andrew follows the signs directing us to our train, car #10. I inspect the wheels as I look for the perfect line in photographs. I am fascinated by the idea that metal wheels on metal rails can and will carry us smoothly across the countryside.

After boarding the train, a friendly stewardess gets us arranged comfortably in our seats. A man slides along the row punching a hole into passenger’s tickets, confirming their belonging in this particular spot in this particular moment of time. Then the train starts to move, imperceptibly at first, releasing one click of its wheels. The weight of the string of cars must be enormous, as the second click of the wheels comes slowly, as if it’s resisting the inevitable. Soon, the wheels pick up momentum and we are gliding along the rails with all the “chug-a-lug” and “clickty-clack” you might demand from a proper train. Andrew peeks out the window to see the cars in front of ours snaking along curves, through the bamboo and banana leaves glowing golden in the afternoon light.

Dinner arrives, and we are offered a tasty duck red curry with sticky rice, and a traditional thai dessert of colorful chewy blobs and watercress in chilled and sweetened coconut milk. A fresh squeezed orange juice, and hot tea on the side. “I guess it’s a little expensive for Thai standards, but...” I say after we’ve traded our dinner money for our little trays of food.

The light dies and there is no longer anything to see outside our window. The man who punched our tickets makes his way down the row re-arranging the space to make two bunkbeds one atop each other. I climb the ladder and take the top bunk as the bottom is just a bit longer to accommodate Andrew’s 6’3” frame. I pop my head I tuck under the blanket, install my sleep mask over my eyes and lay my head on the travel pillow I brought along, and let the rocking of the car and song of “clack-ah-clack” lull me to sleep.

Wake up call for us is an early 4:30 a.m., our stop in the ancient city of Ayuttaya is scheduled for 5:30. I dangle my head below my bunk feeling rather refreshed and cheerful. “Good morning!” I say to Andrew’s still supine form, but then I get a look at his face. Black circles under his eyes, green around his gills. He is obviously in some distress. “Did you sleep all right?” I ask, a little leary to even ask the question.

A small groan precedes the explanation that he has been ill and spend most of the night praying to the train’s porcelin god. “Ew...” I say in response, gathering that a train lavatory is not the place I’d enjoy spending my evening, either. “ExPENSive train food!” I knew that lady had said “expensive” in a funny way. Noted. Noted. NOTED! In these parts, one must pause and consider carefully (meditate on, maybe?) any comment that seems the least like criticism. It’s a survival strategy.

Upon reaching the train station, we try to take a tuk-tuk over to our hotel in the hope to find Andrew a bit more comfort, but of course it was not open yet and there was no one available to answer the door. So, we returned to the train station and found a cozy bench to lay upon, next to a concerned stray dog for company. Soon, the sun rises and the train-station bustles with morning commute traffic.

Eventually, the sun came up, and we made our way to a hotel where the kind owner welcomed us in and got us situated in our room hours before check in time. For this, we were most grateful. Andrew slept off his queasiness, and I got a little blog work done. We couldn’t lollygag around for too long, because Ayuttaya is fascinating in its own right and we had a lot to explore. So, by evening time, Andrew hauled himself to his feet and we started our tour.

The city of Ayuttaya is an irresistible combination of ancient ruins and people going about their daily business. We are greeted with the usual Thai scenery of elephants and bicycles, houses and markets, monks, and old temples built of thin, deeply red hand built bricks. The whole city seems to glow orange under the haze that floats on heatwaves.

We search out the nearest old temple to explore.

We find them alive with travelers, kids running through crumbling doorways, and dogs sitting as sentinels, keeping guard. They are a photographer’s dream, with windows offering interesting frames and layers of temple grounds stretching into the depths.

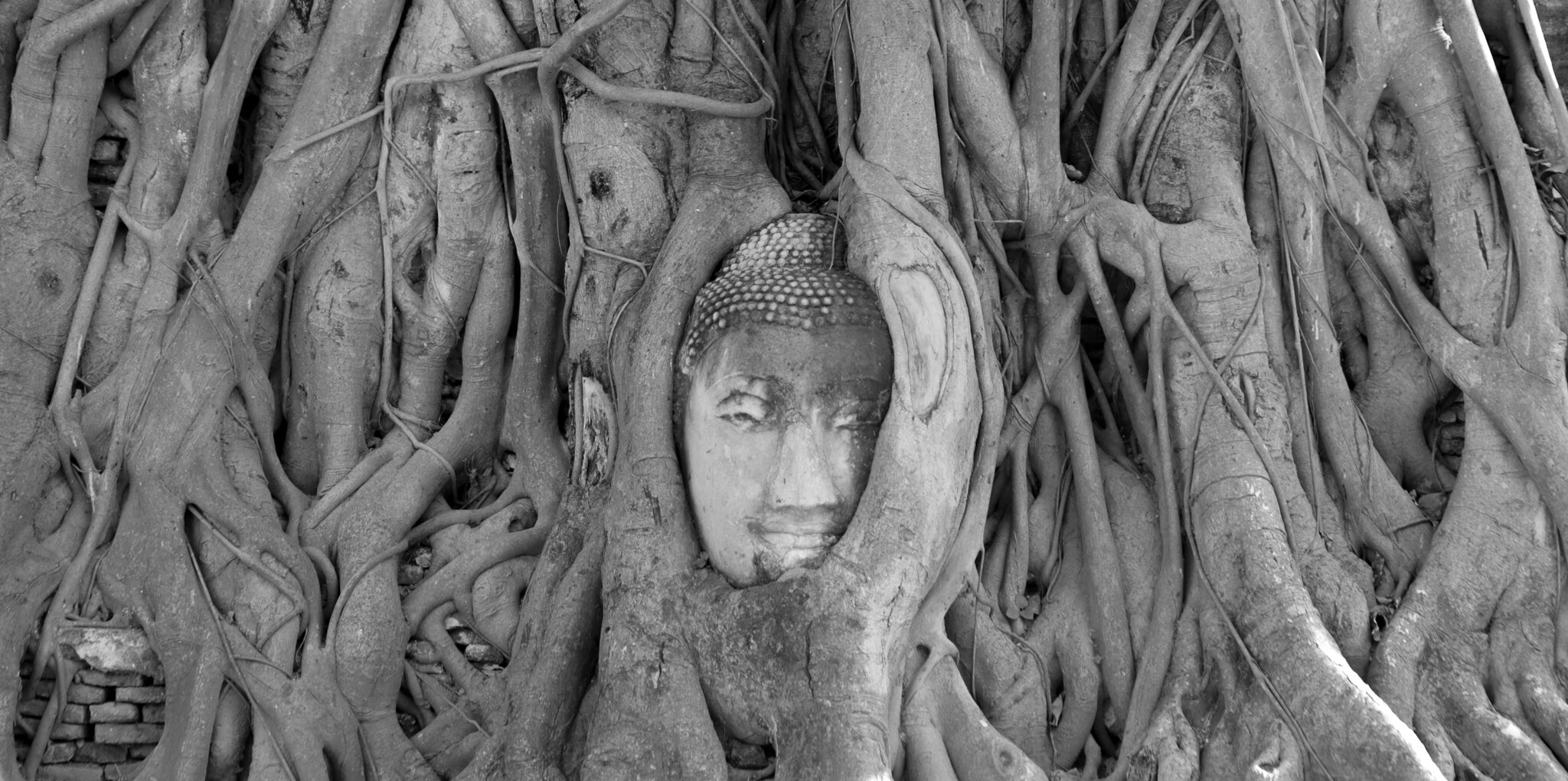

Like the rest of Thailand, Buddhism takes center stage here. But unlike the new, modern art style temples on view in Chiang Rai, Ayuttaya is home to ancient temples from the 1400’s. Many were damaged in repeated wars fending off encroaching Burmese invaders. Heads busts and meditating bodies sit, waiting for their minds to return from the reverie of war that knocked their heads clean away. It’s a little spooky.

As the Buddhists will often explain, Buddhism is not a religion, but instead a “way of life.” This way of life was founded by a prince from Nepal Siddhartha Gautama more than 2,500 years ago. The philosophy has morphed and spread throughout South East Asia to become one of the world largest religions...erm...ways of life.

The major difference between Buddhism and many other religions of the world is the notion that one does not receive the path to “paradise” through the benevolence of god. Instead, suffering ends when you walk the “Eightfold Path” of right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. Buddha is not god, and Siddhartha Gautama is only one Buddha of all. “Buddha” literally means “an enlightened man.” It is the ideal state open to anyone.

“Okay, Buddha,” I say as I read one signpost on the matter. “That’s all fine and well, but how does one define “right....any of those things?” I think to myself.

“A jug fills drop by drop,” A stone Buddha whispers in my ear. Thanks, Buddha.

Everywhere we go, we find lotus flowers blooming from pots or alight with candle flames. For Buddhists, the lotus is a symbolic reminder of their most important ideas - like a crucifix for Catholic Christians. With roots held in the mud of attachment and desire, its flower blossoms on long stalks as if floating above. Drops of water slide easily from it’s petals, a reminder of how peace comes when we allow ourselves to detach and let all things pass as they inevitably will.

“The root of suffering is attachment.” Buddha

The story of Siddhartha has fascinated me since I read the novel by Herman Hesse about the man. Born a prince in Nepal to a wealthy and also wise father, Siddhartha was saddened by the pain and suffering he saw in the world. He renounced his family’s wealth and went into the streets to live as a religious beggar, surviving only on the alms and food given to him by passers by. He became gaunt and ill, but he did not achieve the wisdom he longed for.

He turned the page on that life, and became a wealthy business mogul. He became fat, indulged in food and romance, social competition, and succeeded in reveling in the desires of the day. He fathered a son. And yet, his heart was not content. He did not reach the enlightenment he hoped for.

He sought answers from wise leaders of the time, but their answers never rang true for him. He struggled to reach that moment of clarity or understanding we all know and feel when something clicks inside us and we suddenly “know” or “understand.

Finally, one day, in his frustration, he sat down next to a river beneath a Bode tree, and watched as the water passed by. There, he stayed. Over time, the woman he loved passed by, his son, all of life passed by. Very little followed the path he desired; he recognized his son did not do as he would hope. And this brought him suffering, but he stayed there by the river and beneath the Bode tree: releasing it all, allowing it to pass by the way the river flowed and the tree would shed its leaves.

Buddhists embrace the idea of karma (the law of cause and effect) and reincarnation (the continuous cycle of rebirth). Every time I read the story of Siddhartha, I wonder if the notion of reincarnation is more complicated than dying and returning to life as another creature. I wonder if it encompasses the idea of experiencing the multiple lives most of us lead in our one physical lifetime, or even the spiritual inheritance we pass on to anyone we impact in the future with the way we live our lives today. I feel reincarnated when I pass from one defining experience to another, anytime I discover a chance to be someone different and maybe better than I was yesterday. Sure.

“If anything is worth doing, do it with all your heart.” The Buddha

At the end of his life, Siddhartha felt he had achieved his dream: enlightenment and the end of his suffering. He encourages followers to take “The Middle Way” avoiding self-indulgence but also self-denial. He taught that the process of releasing attachment and finding right understanding is accomplished through meditation one small moment at a time, slowly the way the roots of a bode tree spread and grow.

Our last day in Ayuttaya, we finished our tour at a temple that had been ransacked during one of the many conflicts. The largest Buddha figurine had been decapitated and the head had rolled into the corner next to none other than a Bode tree. As the lore goes, hundreds of years passed by and slowly that Bode tree gathered up the head of the Buddha statute and lifted it upright to be surrounded and supported in the roots as it sits today. What are the chances of that?

“So, what’s your favorite Buddha Quote?” I ask Andrew as we board our next train into the heart of Bangkok.

“People with opinions just go around bothering each other.” The Buddha

Andrew responds.

“He didn’t say that.”

“He did! Look it up.” Andrew insists. So, I look it up on the all knowing inter-webs. Turns out…he did say it.

And, we didn’t eat the train food on this trip.