Our first time aboard a sailboat, ever. (Andrew is behind the camera)

Experiencing what can only be described as a man’s “young-life crisis,” a twenty-one year old Andrew Godfrey puzzled over his latest dilemma: “What should I do with my life?” The path should have been obvious. A recent graduate from university newly minted with his Bachelor of Science in Chemical Engineering, a career in water treatment for industrial power plants awaited him. Why wouldn’t he take up oar and paddle toward his future?

“I need a new goal.” He says aloud to his girlfriend of just one year. I am wrapping Christmas presents as snow begins to fall in our hometown and the former Winter Olympic venue Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, 1,000 miles away from any ocean.

I nod. “Okay, like what?”

“I need something that will inspire me, something to keep my energy up, my purpose driven....”

I nod more, “Okay, okay....” waiting with bated breath for what would be the most unlikely of suggestions:

“What would you think about sailing around the world?”

Any sailor who casts off across an ocean experiences a moment like this. It does not matter that he has never stepped foot on one single sailboat in his life. A sailor at heart will be drawn by the Siren Song even across miles of barren desert and alpine mountain. But how? And more importantly --

How much will it cost?

Lucky for Andrew, he had paired himself up, not with an accountant, or an actuary, or even a mathematician. He had hitched his wagon to a young and easily agitated litigation attorney (a.k.a. Barrister, in the Australian language). While an accountant, or an actuary or a mathematician may have had easier answers for this ever important question, this litigation attorney said (as she should)... “it depends.”

“It depends.”

“Depend on what?” Andrew asked.

“And that is the real question, isn’t it?” I said.

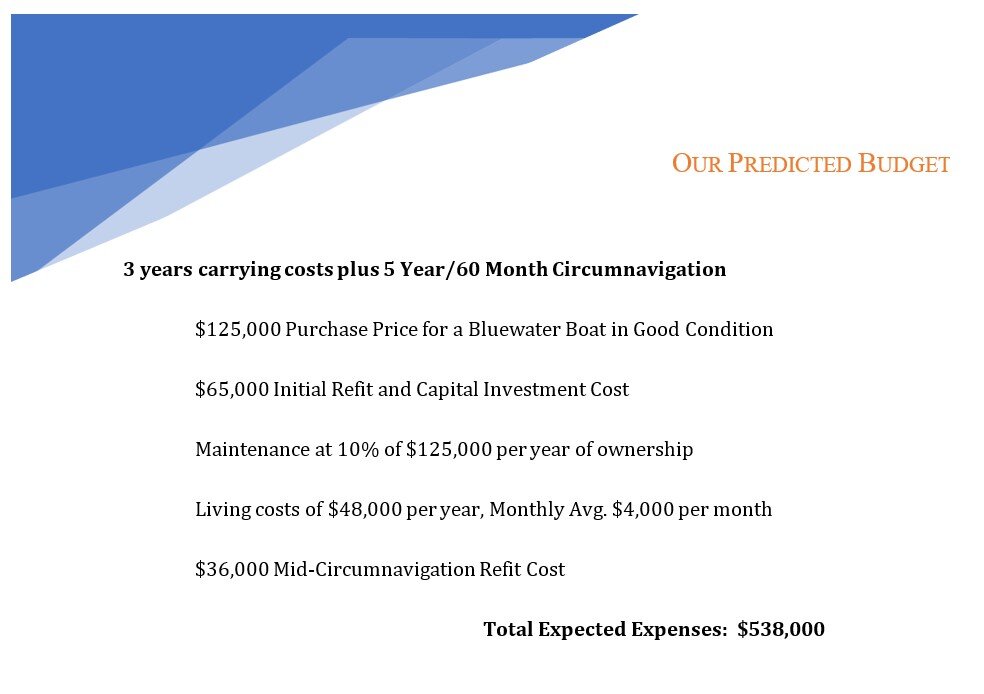

Over the course of the next few years part of our strategy to move from land to sea involved many lessons on how to sail, but we also needed to pin-point exactly (1) how much it might cost for us to accomplish such a dream; and (2) what we were willing/able to do to make that financial goal a reality. Quite sensibly (I thought), our first strategy involved consulting a professional. Dressed in slacks and proper closed-toe business shoes, we sat across the desk inside a well-appointed office of a financial advisor with side-swept thinning hair, a grey suit, and flappy cheeks. He greets Andrew with a handshake saying, "Welcome brother!”

It wasn’t long before this desert-dwelling financial man had pin-pointed our “financial goals,” and he had bad news. He plucked at a keyboard, leaving the colorful wheel on his computer screen to spin as calculations were drawn. He turned the screen toward us to say “you will need to save one billion dollars!” (All amounts heretofore are discussed in US Dollars.) We left that meeting in despair, but it didn’t take long to surmise he cannot be right. There are plenty of other people out sailing already, doing exactly what we want to do. It can’t be that hard.

It can't be that hard.

We started reading books, magazines, and blogs to understand what the sailing lifestyle requires. (At the time YouTube was just the sparkle in some techy-guy’s eye.) Very few sailors shared their dollar by dollar expenses, but we scoured the internet to find as many disclosures as possible. We read the accompanying blog to consider whether those cruisers seemed to live like we hoped to, and we tried to analyze how honest/accurate their data seemed to be.

From this research, we realized the style of a sailor’s trip will determine the cost. A sailing circumnavigation on an eight meter sailboat built in 1973 with no watermaker and a hammock for sleeping accommodations would carry a much smaller price tag than sailing around the world on an Oyster. There are numerous financial factors tucked inside a sailor’s personality and they all impact the budget we had to project. We realized the only way to project our circumnavigation budget is to get clear on what kind of sailors we would like to be. We compiled a list of factors to analyze.

We considered what kind of sailors we would like to be.

We began to analyze our spending habits on land. What is now an excel spreadsheet began as a paper chart taped to our wall. At the end of each day we did the “walk of shame,” dutifully scratching our expenditures into the day’s square and feeling the pain of any frivolous expenditure. Over time, an honest appraisal of our spending habits developed.

We tried to predict the amenities we needed or sacrifices we could make aboard our future ship. We started sailing and tested our theories. We bought a small sailboat, doing all the refit and maintenance ourselves. We went remote wilderness camping to test our willingness for various inconveniences. We chartered sailboats of various sizes, makes, and models in several locations to experience differences between boat designs and sea state. We raced sailboats (as crew), and learned more about the difference between sailing on racing yachts versus slower cruising yachts. By the time we were ready to start our boat hunt, we thought we had a good picture of our expected sailing style.

We then began research on the boat we’d like to purchase. We narrowed our focus to a handful of boat designs that fit our sailing objectives. We did research in our area of the world to figure out the initial condition, purchase price, refit, maintenance, and carrying costs for the boat we needed to match our sailing style.

In 2009, with all this research behind us, we licked our finger, put it into the wind, and made a guess at which direction our budget would blow.

Fill the sail kitty and cast off.

We analyzed our earning rate at the time and calculated out how long it would take to pile up the money we needed. Using the advice of many cruising mentors, we set a cast-off date from which we could not weasel out. There is always something more to be learned, earned, or done before sailing away. So, we pin-pointed February 28, 2016 and set that date in stone. We committed to leave whether we had the money or not. This forced us into discipline, otherwise, we’d be sailing off ill prepared. No one wants that!

By 2012, we purchased our sailboat - a 1981 Valiant 40 - with what we considered to be acceptable refit requirements. We spent weekends over the next three years touching up the refit items and practicing with our “cruising boat” in the open ocean just outside San Diego Bay, California, USA. Our sail kitty hit the full mark just in time, and in February of 2016 we were ready to cast off. Overall it had taken us eleven years from the start of the idea to cast off to compile the money and the skill to go. And we still wondered: would our projections hold up?

Did the projections hold up?

In a word: no.

Our capital investment, refit, and maintenance budgets have been accurate, so far.

Our lifestyle budget, however, is currently running approximately 25% higher than projected.

Our lifestyle budget overruns are not a result of mathematical inaccuracies for cost of living in various destinations. All that usually averages out. Instead, the problems arise in areas where we did not adequately predict our personalities.

First, we discovered we love scuba diving more than we thought we would. The South Pacific has the most incredible water and unique wild-life in remote places I may never reach in my lifetime, again. We couldn’t pass it by without the scuba experience. I’m sure we are not alone in this projection error. The great and terrible thing about sailing around the world is that the planet is even more beautiful than I imagined. There are more “once in a lifetime” opportunities than could ever be snatched up, and we must accept we cannot see and do everything. Even if we had all the money in the world, it still would not be possible.

Second, we are traveling more slowly than projected. The speed and course of our sailing circumnavigation proved itself to be inadequate by approximately the second major stop we made. As Americans with professional careers, we were used to having two weeks of vacation at most. We projected the speed of our exploration route based upon this perspective. “Won’t it be great to spend two whole weeks sailing around French Polynesia?” It wasn’t long before we realized that our style of cruising requires a more relaxed pace. Two weeks might be enough to rest up from passage, find a place to get our laundry done, stock up on provisions, and explore one, maybe two, islands. That time frame is insufficient to do the whole of “French Polynesia” justice.

Furthermore, Sonrisa (our ship) has her own pace that she demands. Often she needs repairs as any cruising yacht will. Usually, Andrew has accurately projected his maintenance schedule and we have spare parts with us on board, but sometimes, an obscure piece breaks or a piece that we did not predict will break at this particular time has problems, and we must figure out how to acquire a new part from afar. One such case recently had us stalled in Langkawi, Malaysia for an entire year! While we had projected funds for the yard costs, labor, and parts expected during a mid-circumnavigation refit, we did not realize we should build in an entire extra year worth of time. We should have realized that if you miss the weather window open for a particular ocean crossing, you have to wait another six months until the cyclone season shifts for you. We are coming to terms with the fact that our five-year circumnavigation looks like it may take six or seven. More time; more money.

Third, we predicted that we would need to return home to visit family and friends twice during the course of the trip and we planned to tuck those expenses into our regular monthly budget. This projection, too, was inaccurate. The first year of sailing was such a shift in my lifestyle that by the time we reached the end of the sailing season in the South Pacific, I needed to return home to visit my family, meet our newest niece, and reassure myself that I am okay with the balance of time devoted to sailing and sacrificed from people I love. I now know my willingness to miss out on weddings, new babies, graduations, my father’s retirement, and worst of all (hopefully not), funerals, is lower than I first anticipated. If I had this to do over again, I’d insert enough money to fund flights home least once per year, per sailor.

And fourth, we recently adopted a ship's cat along with the expenses she entails. I’m usually allergic to cats, so she was never in the projected budget.

I now know these “errors” are to be expected. It is impossible to fully predict every element of your sailing trip, personal style, and future. Learning about ourselves and working with the resulting serendipity is a part of why we went sailing in the first place.

A lucky margin of error.

We are overbudget, but we still aren’t panicking. Why not?

Luckily, back when we were compiling other sailor’s expense reports, we noticed many admitted to editing out “exceptions” they did not include in their disclosures. They deleted expenses associated with trips home, unexpected major repairs, or their personal hobbies, assuming those to be outliers that wouldn’t translate to other people’s sailing experience. We became convinced that “outlier” expenses appear in every sailor’s life. So, we built in a margin of error.

When we set our calculated budget, savings rate, and our cast-off date, we tried to remain conservative. We calculated our savings rate assuming we would never get a raise during the remaining course of our career before castoff (so any raise felt like an added bonus we could add to our sailing fund, just to be safe). And, we set our cast-off date six months further out than the date we thought we our finances would be ready. We didn’t spend the extra money, but socked it away for our “fluff budget.” This extra fluff did not have any line item attached to it, as by definition, it was intended to be used for the unpredictable expenses.

If I had this to do over again, I may also build in a 2-3% factor for cost of living increase. Projections from 2007-2011 and prior seemed to indicate we couldn’t spend $4,000 per month in the South Pacific if we tried, there just wasn’t anything to spend money on there. Once we arrived, we found restaurants, tour guides, scuba opportunities, and all manner of tourism ripe for the spending. What once were remote destinations now have growing tourism industries that are finding ways to charge sailors for their experiences. The world has advanced measurably since our projections were first penned. We are glad we cast off holding approximately a 15% margin of error in our financing.

It's all the adventure.

In addition, as we sailed, unexpected opportunities have come our way. A consulting contract here or there, publication of a book, the strong dollar, a favorable stock market, recovery in the housing market from the 2009 mess we found ourselves in all included. None of these are enough to keep us sailing forever, but just like finding a lucky Yamaha 5HP Outboard propeller tucked away on the jumbled shelf of a Chinese parts shop, sailing life isn't always unexpected expenses. Sometimes, it brings you gifts of income to offer one small shovelful into the pit of expense. These opportunities have kept us within the averages required to get us all the way home so far.

We undertook this circumnavigation as a sabbatical, rather than waiting for our full retirement or trying to remain employed along the way. We plan to return to work at its conclusion. There are reasons for this. We did not want to risk losing the opportunity due to loss of health or an untimely death. It's the “go as soon as possible" approach. We made that choice knowing the strategy carried risk, including vulnerability to insufficient funding. So, what? What if we only make it three quarters the way around the world, then must stop and work somewhere until we can fund the remaining route? What if we must drop our lifestyle demands and alter our trip to sacrifice more expensive land tours, scuba diving, eating in restaurants, or (gasp!) our rum rations until we reach our home port? Those strategies will be part of the adventure. We will figure it out.

And isn't that the skeletal bone underpinning all sailing voyages? A sailor must trust him or herself to find a way.

Celebrating Cast Off

Our friends and family wishing us fair winds and following seas.

Leaving San Diego Bay February 28, 2016